High Trails is located at 7000 feet in the San Bernardino Mountain Range, and one of the first topics we learn about in Team Discovery Hike is who lived here before us. The Yuhaviatam arrived in Southern California approximately 2,500 years ago, and lived off the land until European influence arrived in the 18th century. We move on to learning about FWARPS (Food, Water Air, Reproduction, Protection, and Space) — the resources all living things need to survive. These resources generally come pretty easily to most people in first world countries like our own. However it’s hard not to reflect on how different things must have been for the Yuhaviatam.

One fascinating major difference is the difference in medical practices. Modern Americans who are feeling sick can go to a large sterilized building to get better, but the same was not true of an earlier time. The Yuhaviatam and other Native Americans had only the natural objects around them to solve their problems and ailments. For this, they used a wide variety of local plants. The following is an exploration of four plants local to the San Bernardino Mountains and their medicinal properties. Some of these have been since verified by Western science as effective in their uses, but others do not pass the stringent standards of modern Western Medicine. However they are quite interesting to explore nonetheless!

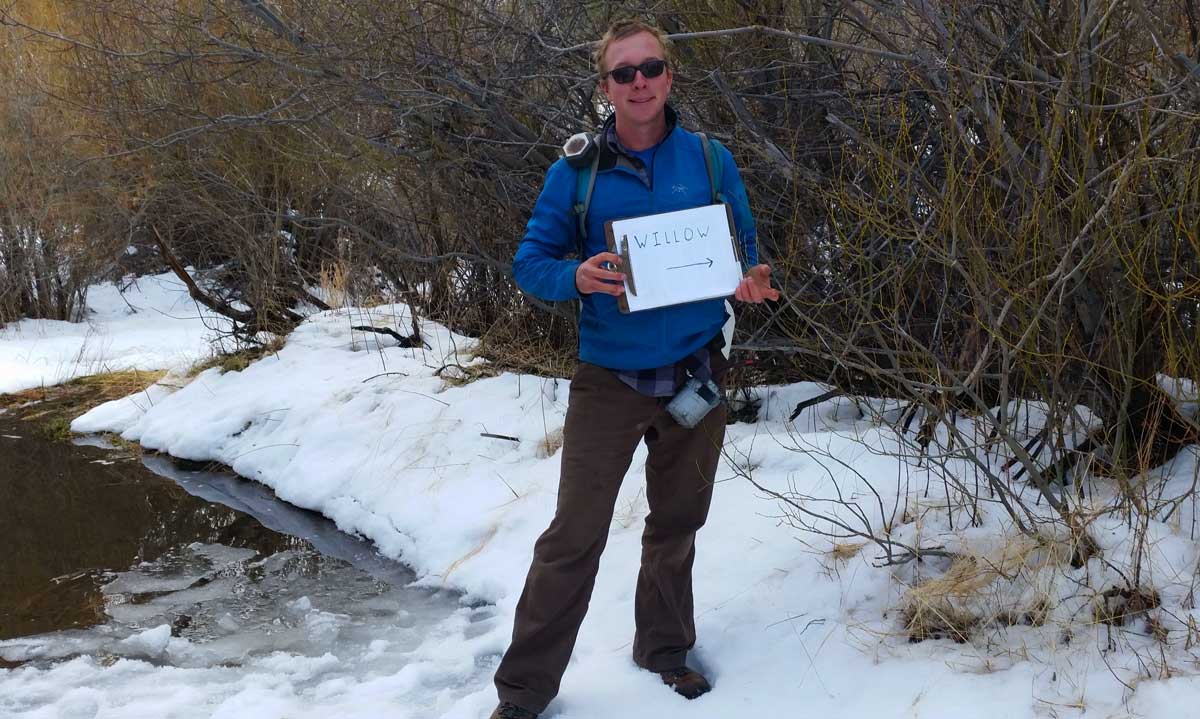

Willow – Salix Spp.

History/Uses: Willow bark has been used for centuries as a pain-reliever and anti-inflammatory. Willow is well-known for treating ailments such as headaches, muscular pain, and fevers. The ancient Greeks used willow to treat joint pain. 1 In fact, today it is used in the synthesis of aspirin! Aspirin has made the pain relieving properties of willow widely available around the world.

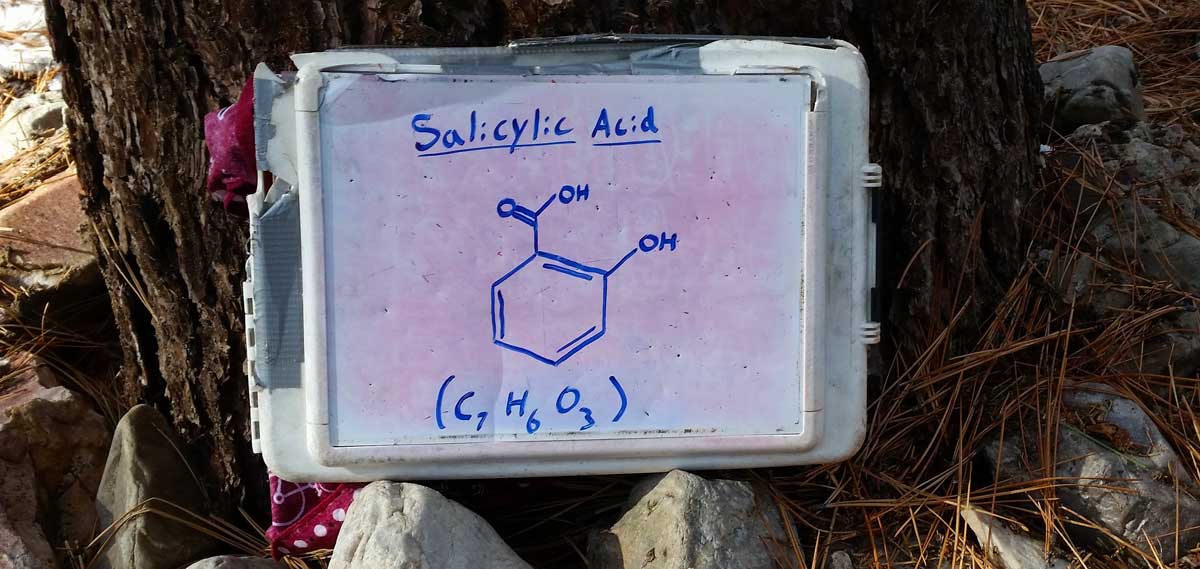

The Science: The scientific term for a pain reliever is an analgesic. This simply means that it reduces pain in a certain area of the body or the body as a whole. Willow bark is used as an analgesic because it has the active ingredient salicin, which the body converts into salicylic acid (C7H6O3). Salicylic acid is the chemical that reduces pain in the body!

Administration: Traditionally, willow bark can be ingested in a few different ways: the most common being chewing on the raw bark or seeping the bark in hot water to make an herbal tea. Different species of willow contain varying amounts of salicin; the most common species used as an analgesic are white willow and black willow. However, do not try this at home!— some species of willow are toxic and don’t even contain salicin.

Location: The two species you might see at High Trails Outdoor Science School are Salix lemmonii, and Salix scouleriana. These species of willow thrive in altitudes of up to 8000 feet, and love the dry conditions of the desert. Willows are riparian species, which means they love growing near water! Keep your eye out for a stream or lake at High Trails, you may just see some willow trees!

Common Yarrow – Achillea millefolium

History/Uses: Yarrow has been used for many years to stop the bleeding of minor cuts and scrapes. It has also been used notably to treat wounds during times of war, for this reason, yarrow is also known as “Soldiers’ Woundwort”. Yarrow is also claimed to be anti-inflammatory, pain-relieving, and antimicrobial. These claims have not been clinically verified, but could very well be true based on its prolific would-healing abilities. Yarrow is also known as “squirrel tail” because its bushy leaves look like the tail of a squirrel!

The Science: The leaves of the yarrow plant contain a chemical which is a styptic. A styptic is a substance “capable of causing bleeding to stop when it is applied to a wound.” The mechanism by which a styptic works is by constricting blood vessels at the site of application. When a blood vessel is constricted enough, especially smaller blood vessels like capillaries, blood can no longer flow through the vessel, which stops bleeding in minor wounds.

There is a common misconception with Yarrow: it stops bleeding because it is a coagulant. This is untrue. While both do stop bleeding, coagulants stop bleeding by inducing blood clotting. Blood clotting is when platelets (a type of blood cell) thicken the blood from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot which stops bleeding.

Administration: The styptic properties of yarrow are found in the leaves. The most common application is topically, which means directly against the skin. The fresh leaves are crushed slightly to release some of the juices, then the leaves can be directly applied to a wound. This application can be done directly from the fresh plant itself, even mere moments after picking the plant.

A salve can also be made in advance from yarrow leaves. A salve is an ointment or cream that is applied to the skin. The yarrow salve is made by first drying the leaves, then grinding them into a powder. This powder can be stored until it is ready for use, at which time water is added to the powder and applied to the skin.

Location: Yarrow is actually a weed, which means it’s really good at growing in a lot of environments. Yarrow can be found growing throughout North America. It has been found in all 50 states! In California, it is found in every habitat, except in the Colorado and Mojave Deserts. 3 Yarrow prefers to live in non-wetland areas, like meadows and grasslands, but can truly be found anywhere!

Sagebrush – Artemisia spp.

History/Uses: The leaves and smoke of the sagebrush plant have antimicrobial properties. For this reason, the smoke from burning a bundle of sagebrush leaves was used to fight respiratory tract infections. Some southern Californian Native American tribes have been known to use sagebrush in this way, such as the Kumeyaay and Cahuilla tribes, and tribes all across North America have used varieties of sage in this way. 4

Sagebrush and other sages have a long history of being used as a cleanser and purifier as well. In many traditions, burning sage clears out spiritual impurities within a space. For this, a bundle of sage was burned in indoor or outdoor areas to purify that space. Often this was done when arriving to or departing from a new location.

Sage leaves have also traditionally been dried to then be smoked during ceremony. This is similar to the leaves of the tobacco plant, another sacred herb in many traditions.

The Science: Sage leaves have antimicrobial properties. This means they kill bacteria, prevent their growth and reproduction, or both! The term can also be applied to viruses and fungi as well, in addition to being effective against bacteria. Sage leaves are effective against all three!

The spiritual aspects of this are unscientific in nature. “Purify” is a vague word that is difficult to pin-down scientifically. There is no scientific basis for sage cleansing spirits and bad omens, however it is interesting to think that this tradition is so widespread across much of North America, with much overlap among faraway tribes, with no contact. As with any ritual or ceremony, everything is given a deeper meaning if done with intention.

A closeup of a sagebrush stem with many sage leaves.

Administration: Sage was mainly used to purify spaces. This was done by first drying the leaves and tying them in a bundle. This was done by smudging the sage. Smudging means to burn with a small ember, without an open flame. This ensured that the sage leaves would burn slowly for a long time, while producing a lot of smoke!

Location: Sagebrush can be found all across the midwest to western United States. It prefers a dry climate, so often finds its home in arid areas and at mid to high elevation. At High Trails, you will likely find Big Sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), look for it at our Oakes site!

Prickly-Pear – Opuntia Spp.

History/Uses: Native Americans in the southwest United States and Mexico would use the raw pads of the prickly pear cactus to treat burns. It would also be used to promote the healing of open sores, by keeping them moist in the often dry conditions.

Prickly pear also has a long history in traditional Mexican folk medicine in the treatment of type II diabetes. 5 Though at the time it did not have the name diabetes.

Of course the main use of prickly pear cactus was not medicinal— it was eaten as food! The fibrous insides of the cactus were very nutritious, and would often be cut into strips and boiled or fried.

Smaller prickly Pear cacti are found at High Trails.

The Science: One common side effect of diabetes is hyperglycemia, or high blood sugar. This is when there is too much sugar in the blood from past meals, and the body cannot process it and remove it from the blood. Normally, the body produces a chemical called insulin to metabolize the sugar in your blood. Metabolization means converting the sugar in the blood into energy for the body to use.

There have been many studies on prickly pear cactus, and the general consensus is that it does indeed have “anti-diabetic” or “anti-hyperglycemic” properties (this means it works well to treat diabetes!). 6 However, it is currently unknown as to how prickly pear cactus actually does this. One hypothesis is that the cactus has chemicals inside it which are very similar to insulin, and thus promote metabolism of sugars in the same way insulin would. Another hypothesis is that it increases the efficiency of the insulin already in your body, by increasing the number of spots in can bond to. But more research is needed to discover the exact reason why prickly pear is effective to treat diabetes. It’s a scientific mystery that we still don’t know the answer to today!

Administration: To combat diabetes, the prickly pear cactus is simply eaten. This means removing the barbs of the cactus, and peeling off the skin (the skin is technically edible, but is typically removed). At this point, the prickly pear can be prepared many ways, but it is typically boiled, fried, or pickled.

For wound care and burns, the pad of the cactus is cut open and applied topically (directly to the skin).

Location: Prickly pears are members of the cactus family, and as such they prefer dry, hot, and sunny conditions. There are species found in Europe, Mediterranean countries, Africa, southwestern United States, and northern Mexico. Your best bet for sighting these cacti at High Trails is at our Oakes site, which is arid and gets more sun. Look for them on south-facing slopes with plenty of sun!

Prickly Pear cacti can grow quite large under the right conditions!

That’s all folks! I hope you learned something new about a plant all around us in Southern California. I love investigating like this because it gives me a new lens with which to view plants that I see around me every day! As I do my walks around High Trails with my students, I am constantly fascinated by what powers are hidden within all plants. Each holds some use beyond what can be seen on the outside. It is fun and illuminating to learn about what potential is stored in the plants around us as we walk through these wonderful woods.

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

- https://extension.umd.edu/sites/extension.umd.edu/files/_docs/programs/master-gardeners/Montgomery/2018SpringConference/1%20Evolve%20with%20Your%20Native%20Herbs.pdf ↩

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/90/Yarrow_dark_backround.jpg ↩

- https://www.calflora.org//cgi-bin/species_query.cgi?where-calrecnum=61 ↩

- https://www.sandiego.edu/cas/biology/kumeyaay-garden/plants/cal-sagebrush.php ↩

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6572313/ ↩

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6572313/ ↩

Comments are closed.