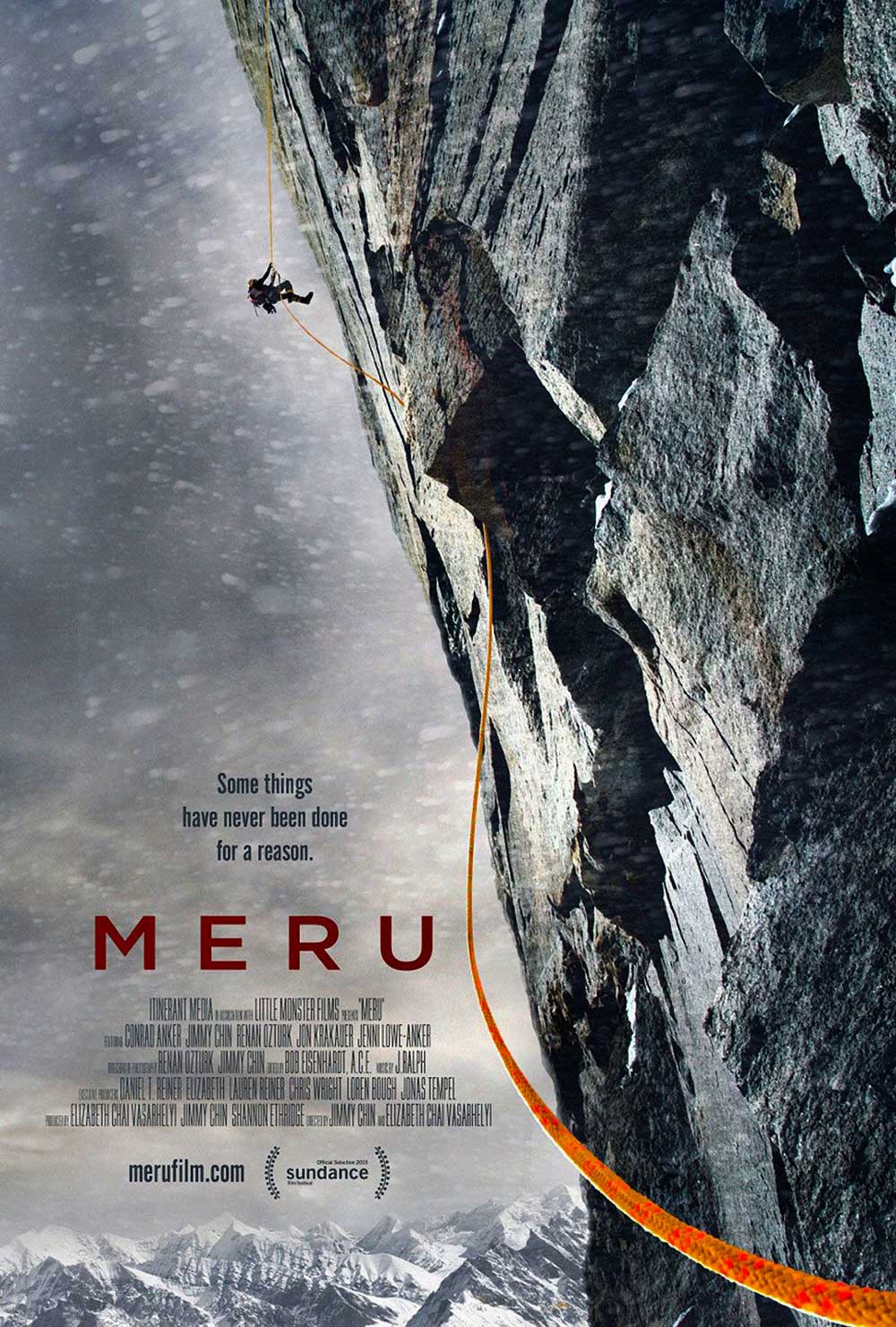

In Northern India, stationed unassumingly over the sacred headwaters of the Ganges River, stands the Shark’s Fin on Mount Meru. This particular piece of mountain has witnessed more failed summit attempts by elite climbing teams than any other ascent in the Himalayas which makes this particular climb both a nightmare and an irresistible calling for some of the world’s most seasoned climbers. Meru is a 2015 documentary film chronicling not only the first ascent of Meru but also the sacrifice, obsession, failure, and friendship that went into this journey.

The documentary starts in 2008 with Conrad Anker, Jimmy Chin, and Renan Ozturk hatching a plan to summit the Shark’s Fin. Anker spearheads the conversation, convincing Chin and Ozturk to join him on this journey. Mugs Stump, Anker’s climbing mentor, once tried and failed to summit this particular 4,000-foot-tall rock, before tragically passing away in a climbing accident in 1992 while guiding a trip. Anker felt not only a particular desire to summit the Shark’s Fin to posthumously fulfill his mentor’s dream but also to test his own skill as a mountaineer and rock climber.

In October of 2008, the team of three set off for an attempt at the Fin. To undertake Meru, according to John Krakauer, bestselling author of Into Thin Air and mountaineer himself, “You can’t just be a good ice climber. You can’t just be good at altitude. You can’t just be a good rock climber. It’s defeated so many climbers and maybe will defeat everybody for all time. Meru isn’t Everest. On Everest you can hire Sherpas to take most of the risks. This is a whole different kind of climbing.” What Anker, Chin, and Ozturk were looking at attempting was to haul 200 pounds of gear up 4,000 feet of technical, snowy, mixed ice and rock climbing. After that approach, the team would make it to the Shark’s Fin itself: 1,500 feet of smooth, nearly featureless granite. The 2008 plan was to summit in 7 days but a massive storm brought 10 feet of snow and sub-zero temperatures, forcing the team into a harrowing 20-day battle, ultimately ending in failure, just 100 meters from the summit, the closest to the summit any team had ever gotten. They returned from the expedition with trench foot, malnourishment, the inability to walk for weeks, heartbreak, but, most importantly, their lives.

Anker, Chin, and Ozturk

Anker, Chin, and Ozturk returned to their regular lives, initially convinced that they would never attempt Meru again. They had set a goal and failed, which gave them the space to reflect on the motivations of their trip.

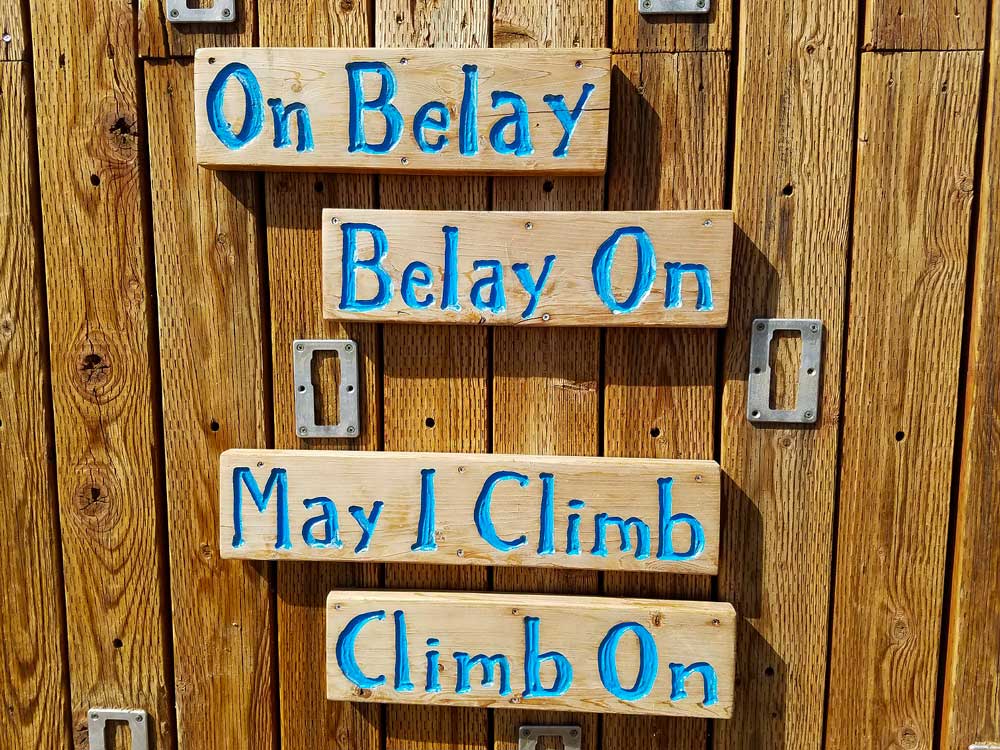

Each week at High Trails, we ask and encourage students to set goals for themselves both as individuals and as a group to demonstrate the power of combined effort and will to accomplish something impressive. Sometimes we set the goal for them, like the combined Food Waste Goal at breakfast and dinner. Other times we let them set goals for themselves, like at the climbing wall. We introduce the activity as challenge-by-choice, meaning they can set whatever climbing goal they want, as long as they give it their 100% – all their effort. We ask the students to let us instructors know what their individual goals are, so we can help them to reach their goal. Sometimes the students make it to their goal. Other times they underestimate and reach way past their goal. The rest of the time, they overestimate, try, and fail to reach their goal. Regardless of the result, there is always something to be learned from each scenario, making climbing a personalized growth experience.

If they met their goal, great! When asked, maybe next time they’ll want to try climbing something more difficult, or climbing faster, to push their limits. If the student underestimated their goal, then they learned that they can set their sights higher and to have a bit more faith in their ability. My favorite scenario is when they overestimate, because they are shown in a tangible way that they bit off more than they can chew. Climbing has a visceral way of showing students that some goals aren’t as easy as it might appear, and everyone’s way of approaching the same challenge will be different, because everyone’s strengths are different. With each student who asks, “On Belay?”, and “May I Climb?” the wall asks them in turn, “Who are you?” and “Why are you doing what you are doing?” I think it’s special to provide each student with a moment of self-inspection, however fleeting, and whether or not they notice it. Every student who attempts to climb our walls are given a chance to decide who they are, what they want, and what kind of person they want to be.

The questions that our climbing wall asks our students are the same questions that elite climbers face on every cliff face and every expedition. And these are the same questions that faced Anker, Chin, and Ozturk after their failed summit attempt in 2008. They spent time by themselves and with loved ones, recovering and pondering what this experience meant for them. Who are you? Why do you do what you do? Who do you want to be?

Hi. I am Grace!

Anker, even before returning home after the first attempt in 2008, was already plotting another attempt at Meru. Anker climbs because he loves it and otherwise he’ll go crazy, unable to answer the siren song of the mountain peaks.

Ozturk’s answer came to him differently. While backcountry skiing and filming for a commercial project, Ozturk suffered a near-death injury. He severely fractured his skull, broke two vertebrae in his neck, and severed a vertebral artery, cutting off half the blood flow to his brain. The surgery, while risky, was successful and Ozturk survived. Just days after his surgery, lying in his hospital bed, Ozturk decided that his goal would be to go back to Meru, in 6 months time. Ozturk said, “For me, it was worth the risk. It was something that I had to do. It was worth possibly dying for.” Even when faced with death, he decided that he couldn’t live without climbing.

Not long after Ozturk’s ski accident, Chin was buried in a massive avalanche and miraculously survived being tossed 2000 vertical feet down a mountainside by snow. Chin withdrew from outdoor pursuits but he also emerged, ready to try a second attempt at summiting Meru. Chin said, “Just thinking about not skiing and not being in the mountains…I wasn’t ready to give it up yet.”

On their second attempt in October 2011, Anker, Chin, and Ozturk were the first team to summit the Shark’s Fin. For our students and our climbing wall, reaching the initial goal is not always the end and the expected lesson is not always what they find. Every student gets an opportunity to discover something new about themselves by climbing the wall.

DISCLAIMER: This documentary film is rated R for strong language and may not be suitable for children.

Sources:

- Chin, Jimmy and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, directors. Meru. Music Box Films, 2015.

- http://www.alpinist.com/doc/web11f/newswire-meru-sharks-fin-anker-chin-ozturk

- http://www.merufilm.com/

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

Comments are closed.