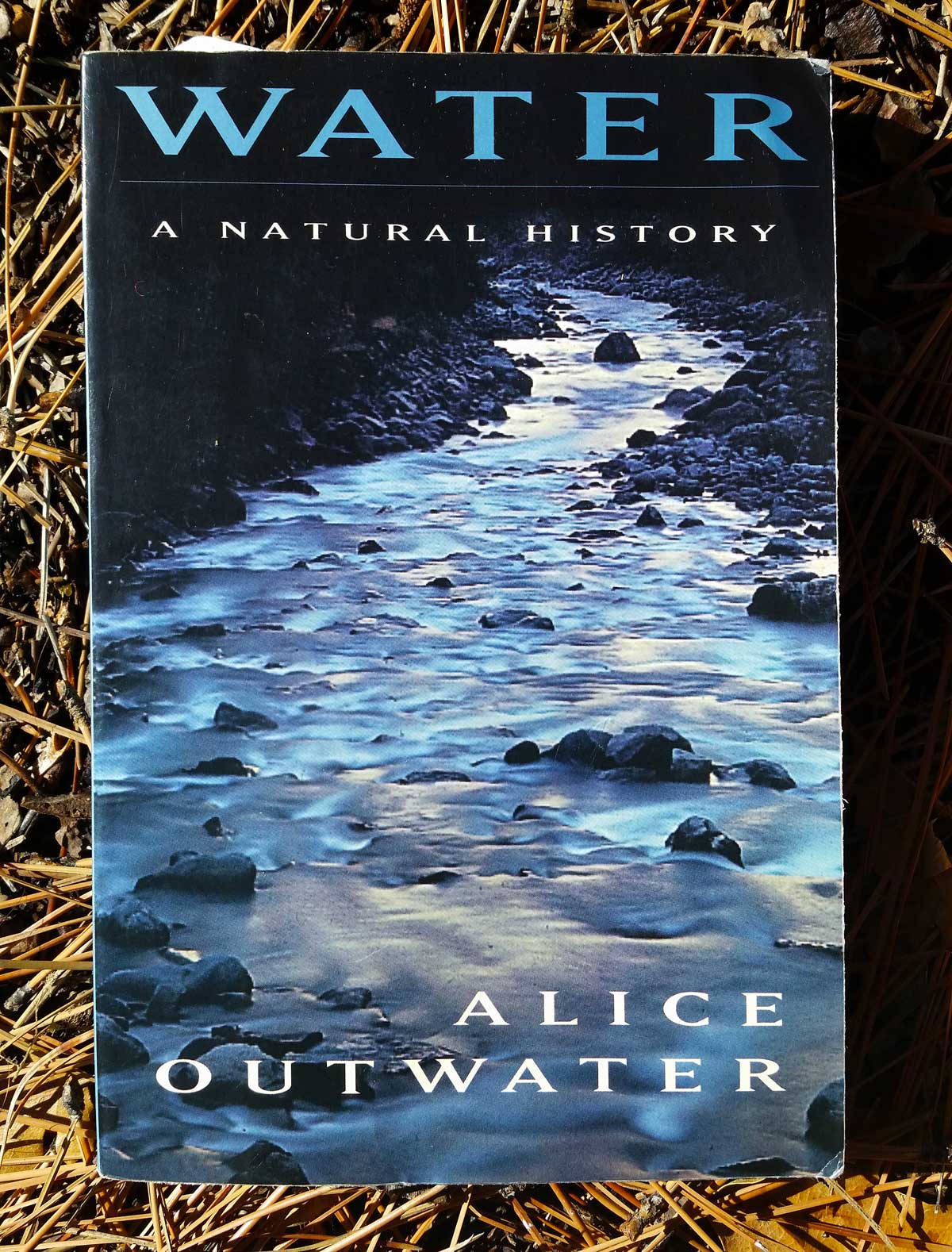

Water: A Natural History, by Alice Outwater, is a thorough guide to how humans have dismantled the fragile water systems of the land, and has added so much more depth to my Water Wonders classes.

Our class Water Wonders, one of my favorite classes to teach, contains not only basics about the water cycle, where drinking water comes from, and discussions about conservation, but also lessons about different types of water pollution and a final experiment showing how normal human activities can pollute drinking water. This experiment tends to leave students with a lasting impression that I often see reflected in their end-of-week evaluations with comments such as “I learned that it’s easy to make water polluted and we don’t have a lot so we need to be more careful.”

Dismantling the Natural System

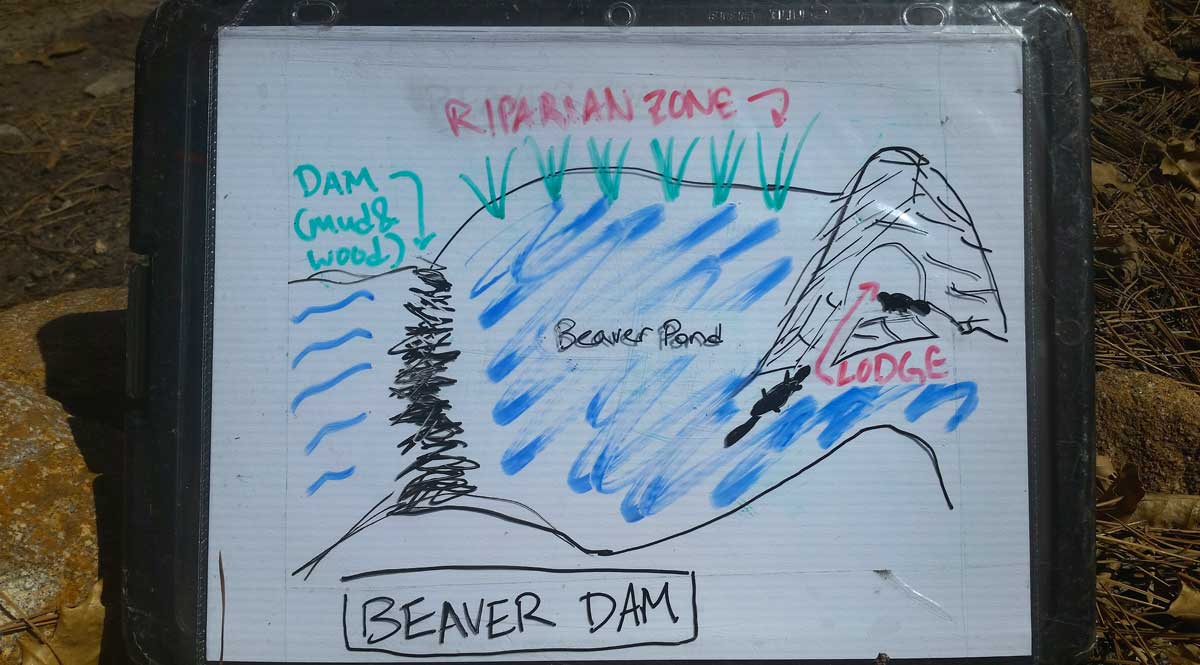

Part One is entitled “Dismantling the Natural System” and focuses on early European influences on the waterways. When we think of water pollution, the image that comes to mind is often a black smoky factory spewing oil and chemicals into a river. However, disturbing the natural systems actually began far earlier than that, and this book begins with a chapter on the fur trade, the lucrative business that brought Europeans into what would become Canada and the northern United States. Surprisingly, trapping beavers from the mid 1600s to the early 1800s had a detrimental effect on beaver populations, and by 1840, the beaver was very nearly extinct. This did not just affect beaver and fish populations, as beavers do more to shape the land around them than any other mammal except humans. They make dams to have home ponds to fish in and good places to raise their young, but these dams also create wetlands and meadows, full of rich organic material and diverse and robust riparian zones.

Riparian zones are where land meets the edge of a river or lake, and they are generally incredibly biodiverse! These areas create dense food webs, including frogs, birds, insects, algae, and mammals, since places with both plentiful water and food are magnets for all living things in the area. This balance of life in wetlands does a very good job of cleaning the water, as plankton feed off organic contaminants and water filters slowly through the natural sediment, almost like straining it through a cheese cloth. Not only do wetlands clean water, they also act to reduce flooding and erosion by absorbing excess water during wet times and releasing it during drier times. Once the beavers were nearly wiped out (although the population is recovering, it is nowhere near the numbers they were at prior to 1600), these wetlands disappeared, making the water less clean, erosion and flooding harsher, and biodiversity plummet.

Beaver trapping was not the only early effect that Europeans had on the water. Water is also cleaned and regulated by forests, which were logged with rapid abandon, and grasslands and prairies, which were plowed into farmland. All the resources of the New World were seen as infinite, the land so vast and untouched compared to the Old World that it seemed a treasure trove of timber, farmland, furs, and room for the Manifest Destiny of expansion. Although it is possible for us to do a lot of damage very quickly with modern chemical pollutants, we cannot forget how quickly and thoroughly settlers demolished old-growth forests and grasslands as they headed west across the United States. It would be ignoring history to focus solely on factories as the cause of our planet’s crisis, and Outwater shows us step-by-step the damage this process had on the water systems.

Engineering the Waterways

Finally, Part Two, “Engineering the Waterways” tackles the effect of industry and infrastructure on further damaging the waterways. It begins with the Bureau of Reclamation’s ambitious projects to dam rivers for water storage and the disastrous effects on fish, then leads into a chapter on freshwater mussels, their role in the ecosystem, and what happened when they were eradicated. Again on the list of historical businesses I would not have thought would affect the water: pearl button factories in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

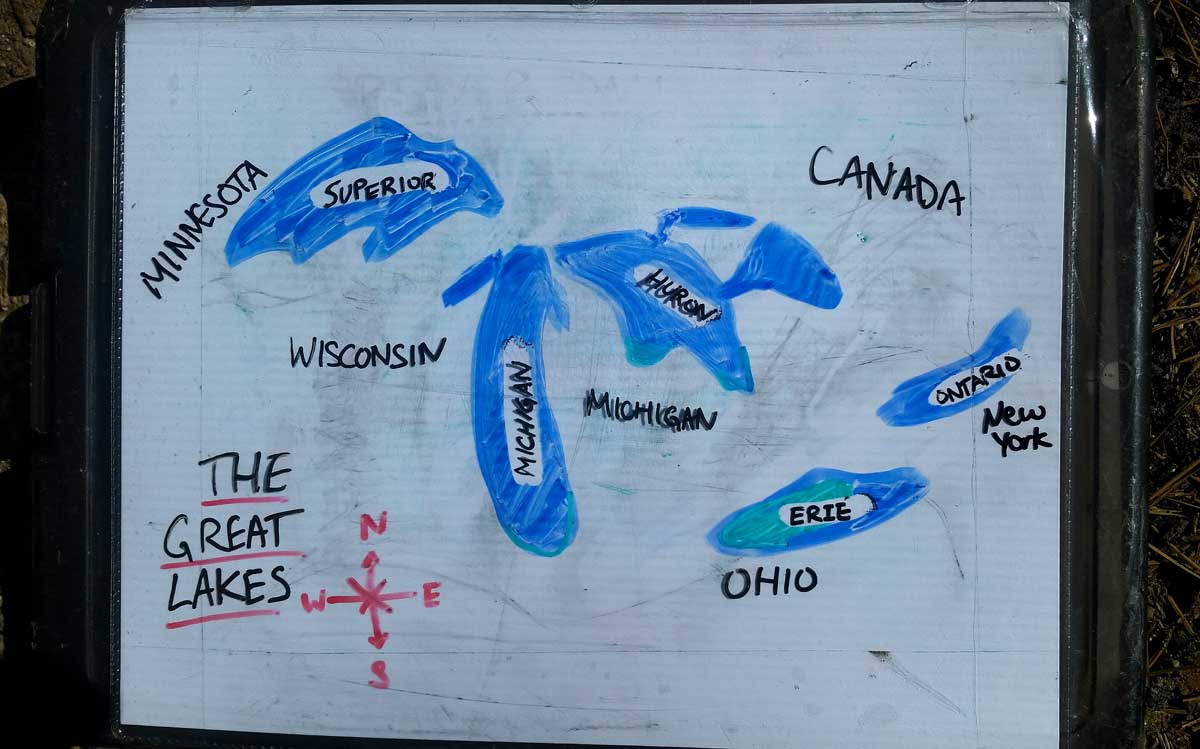

My favorite chapter in Part Two is chapter ten: Down the Drain, Up the Stack, which chronicles the advent of chemical pollutants in rivers and lakes. It contains many concepts that are central to the Water Wonders lesson plan and illustrates them in greater detail, including biomagnification (of DDT, PCBs, and mercury), organic pollution from fertilizers as well as phosphates from detergents (which cause algae blooms and low oxygen saturation just like fertilizer does), and even the smogulous fate of Lake Erie, which we discuss every week at the Lorax.

By 1958, a large section of central Lake Erie had become completely anoxic – the phosphates and fertilizers had stimulated enormous algae growth that choked out most other life, and organic matter being broken down by small decomposers took oxygen out of the bottom layers of the lake. Meanwhile, every stream that fed Lake Erie was extremely polluted by the heavily industrialized area, including the Cuyahoga, which was so clogged with chemicals, oil, and trash that it actually caught on fire in 1969, burning down two bridges in Cleveland in a “toxic inferno of flames some 200 feet high.”

The end of Water seems to paradoxically bring hope as it informs us scientifically of the doom of the water system.

While some parts of this complicated, interconnected water system we live amidst seem irreparably broken, others seem to be healing slowly. Just like we tell our students at the end of the Lorax, Lake Erie is not the polluted fire hazard it used to be. Happy endings are possible, and the more we know about the water system’s natural balancing act, the more we can help restore it to its former health.

The will to restore the land is there, Outwater says, and celebrates that some filtering mussels (invasive though they may be) are starting to return, as well as the buffalo, and people are beginning to understand the importance of prairie dogs and beavers to the land and water’s health. I endorse a thorough reading of this book, preferably in a hammock or by a river, both to improve teaching Water Wonders (if you are a High Trails instructor!) and to give you hope and enlightenment in a frighteningly fragile world.

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

Comments are closed.