In sixth grade I remember losing a spelling bee because I did not know how to spell ‘hypothesis’.

Our science teacher, Ms. Miers, had spent the entire fall semester pounding the Scientific Method into our heads and yet I still did not even know how to spell hypothesis. From that one humbling moment on, I have made a point of not only knowing how to spell all the steps of the Scientific Method but also look for opportunities to use this process in my everyday outdoor education life.

Scientific Method opportunities present themselves often when teaching in the outdoors.

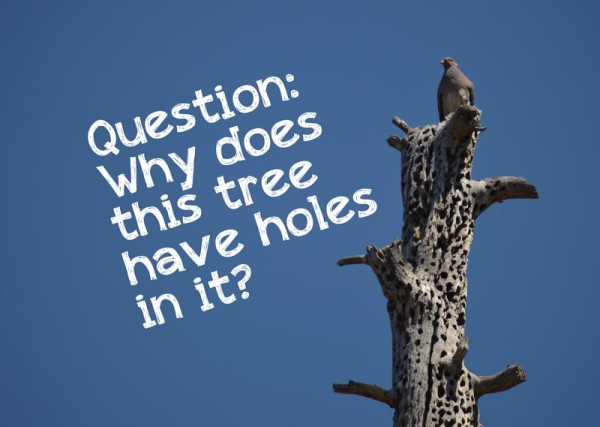

From hypothesizing why a tree has hundreds of similar sized holes drilled in it to analyzing graphs of data to conclude what the carrying capacity of an ecosystem is. The purposes to that seemingly silly activity of building a town out of pine cones or game of Nitro Tag are extensively explained.

From hypothesizing why a tree has hundreds of similar sized holes drilled in it to analyzing graphs of data to conclude what the carrying capacity of an ecosystem is. The purposes to that seemingly silly activity of building a town out of pine cones or game of Nitro Tag are extensively explained.

With all of this, you can imagine my pleasure in watching Mrs. Wright’s sixth grade class at North Shore Elementary and realizing that not only is science woven throughout their day, but also these students are actively using portions of the Scientific Method throughout the day as well.

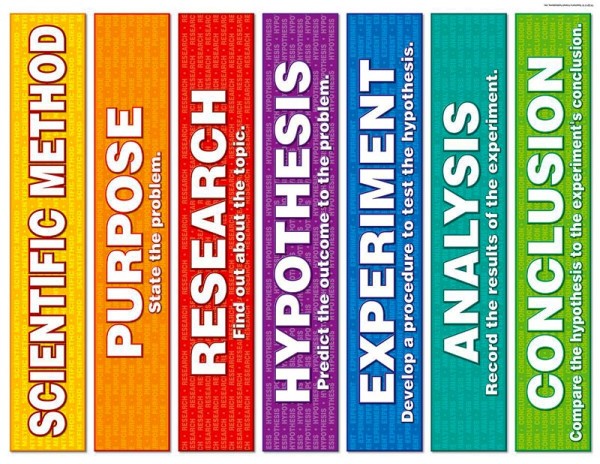

In case you need a refresher, there are six steps to the Scientific Method: Purpose, Research, Hypothesis, Experiment, Analysis, and Conclusion. Each step was woven into the school day seemingly seamlessly.

Below is example of how the students of Mrs. Wright’s class were doing each step of the scientific method and tips to intentionally incorporate the Scientific Method into life at High Trails.

Purpose:

Purpose:

Before the students arrived for the day Mrs. Wright had written the purpose of both the science and math lessons for the day. As concepts were introduced or reviewed, Mrs. Wright was very honest with her students about the common core standards they met and the reality of why they needed to know something.

This straight forward approach to admitting what is required works well at High Trails also. When students understand the weight and power behind the information of why we aim for zero food waste in the dining hall or why the student needs to understand the terms abiotic and biotic, students are more likely to have the message stick. The information becomes not just ambiguous facts that are not connected to anything; instead they have meaning and power behind them.

Research:

Research:

The class looked at USGS’s Earthquake Monitor, both the worldwide view and the California view. After hypothesizing how many earthquakes happened on earth in the past 24 hours, the students noticed that multiple earthquakes occurred in the Big Bear area of California that day. Not content to just let that pass, they did further research to realize that there had in fact been three earthquakes in the area, however the largest one had only measured 1.6 on the Richter Scale. All of this information was filed away so on future days when they again looked at the Earthquake Monitor they would have a point of reference.

As instructors we are the fountain of knowledge that the students use to do their “research” on our forest. The more information we know – from earthquakes in our area to medicinal properties of local plants to scat or track identification, the more the students will have to add to their bank of knowledge.

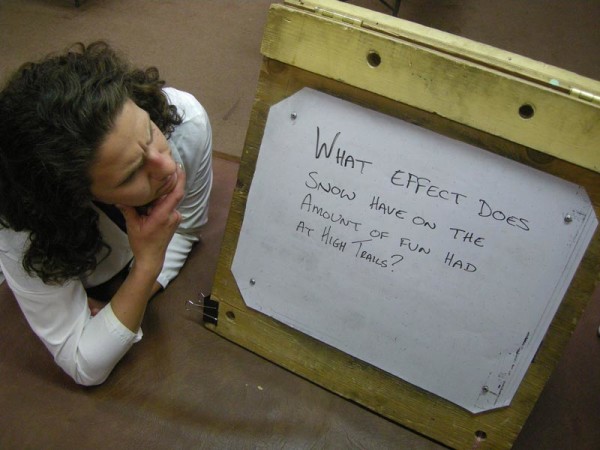

Hypothesis:

Hypothesis:

During reading, the class has been reading “The River” by Gary Paulson aloud. At a crucial point in the book where the protagonist is looking at a map trying to figure out the quickest way to get help into the wilderness for his friend in a coma, the students paused their readings, looked at the map themselves, and predicted various ways that the protagonist could succeed.

The book’s title gave a clue to how the protagonist survived, but that moment of critical thinking and independent thought kept the students engaged. This is an important tip to remember at High Trails as students become distracted by the surrounding forest, sometimes the easiest way to pull them back in is to pose a thoughtful question about the surrounding area and watch them explore to figure it out.

Experiment:

Experiment:

During math, the students were working on mean and median. Instead of taking a written test, they will be doing a performance task assessment. Given a bag of various colored beans or “fish,” the students will have to draw a sample of the beans to determine the ratio of black vs. white “fish” in their “lake.” Along with basic numerical analysis of the data such as median or mean, the students will also be creating histographs and make suggestions for the management of their “fish” populations. The students will be conducting a little experiment, working their way through the scientific method. All of this is in preparation for creating science fair experiments and projects in the winter.

At High Trails, many instructors use a point reward system for positive answers/discoveries/behavior or a trash collection incentive that carries over from day to day. Adding in a mini research project that similarly spans the whole week could function in a similar way but directly apply to the science the students are learning. Students could conduct a research experiment counting the number and species of fallen trees they see on hikes. Data could be graphed, analysis conducted, and conclusions reached creating a continuity across lessons and the students’ time at High Trails.

Analysis:

Analysis:

The students worked with various sets of data: daily high temperature for Big Bear Lake, price of shoes, ages of people at a movie, scores on a science quiz. At each station the students used a whiteboard and dry erase marker to find the median and mean of each set of data. The concept was simple and the process was repetitive once nailed down, however the mixing in of real world examples and the hands on approach of the white boards kept the students engaged and excited about the analysis.

At High Trails there is analysis of data or information in all of our classes. However, it is important to remember that the students need to take ownership of this analysis. While asking them to assess the survival rate of trees without the proper resources or determine why stars look to be different colors, we as their instructors need to give them the time to work it out for themselves – sharing with a neighbor, quiet reflection, or tools to draw or write to express themselves are sometimes needed. Time management comes into play here, but students will remember more if they do it themselves.

Conclusion:

Conclusion:

Using the data sets mentioned in the Analysis section, the students were asked to draw conclusions beyond just the median and mean. For example, what type of movie was playing that created such a wide range of ages in the theater? Why did the price of shoes vary so much? Many of the students were eager to take the time to think and actually come up with thoughtful and inventive responses because they were already invested in the problem. The students were invested because they had had ownership of all steps of the process – from figuring out the purpose to hypothesizing the outcome to determine the right formula to use to gathering and analyzing data.

Having students draw big picture conclusions from High Trails is the end goal for all instructors, yet sometimes the students just stare back at you with blank looks.

Many times this happens when the students have not been actively participating throughout the rest of the lesson. Although we have many hands-on experiential moments mixed in amongst the lecture portions of our classes, the prevalence of these activities causes us to sometimes forget to make the lecture portions more engaging. By having students draw along on their paper what we write on our white board or bringing in real world examples of types of rocks or plants the students can hold and physically see the concepts we are teaching, the students can become more engaged throughout the lesson. This leads to a level of investment that the students use to create consequential conclusions.

Introducing the concept of the Scientific Method and its steps is an interesting way to frame our teaching at High Trails. By intentionally trying to incorporate the Scientific Method into our lessons, students will have a greater sense of ownership to the information and ideally have a bigger take-home message that will stick with them long past their time at High Trails.

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

Comments are closed.