Fungi finally get their 15 minutes of fame here at High Trails as we teach our class Little World. This is just fine with me, as fungi were hugely important to my family’s world when I was growing up; they were food, fun, and a connection to the outdoors.

Yes, that’s Chehala as a kid having some fungi.

Chehala, fungi loving outdoor educator.

As a kid coming to age in Washington State, the environments around me were hotspots for delightful, edible fungi just waiting to be sustainably harvested.

Before I knew how to walk, I was learning the ins and outs of where to find Golden Chanterelles (Cantharellus Cibarius), Black Morels (Morchella), King Boletes (Boletus edulis), and more; and how to identify those species from nasty, deadly look-alikes. The fall rains west of the Cascade Mountain Range, and spring wildfires and dry heat east of those mountains brought with them those fungal delicacies that made our taste buds dance with delight.

Now, as an educator, and a human wishing to do well by our Earth, I see mycology (the study of fungi) as a key step in the path towards a better world. As a species, humans have taken a toll on the Earth; and because of that, scientists and mushroom enthusiasts including Paul Stamets (author of Mycelium Running: How mushrooms can help save the world) , have begun diving into how humans can harness these mycorestorative properties to help solve some of the problems that humans have had a hand in creating.

Mycorestoration is a term used to describe the process of using fungi to repair weakened environments and ecosystems.

This little part of our world, fungi, can make a big differences by helping to restore fire damaged areas and act as a filter to remove harmful chemicals from both our soil and water.

Fungi and Fire Restoration

Fungi and Fire Restoration

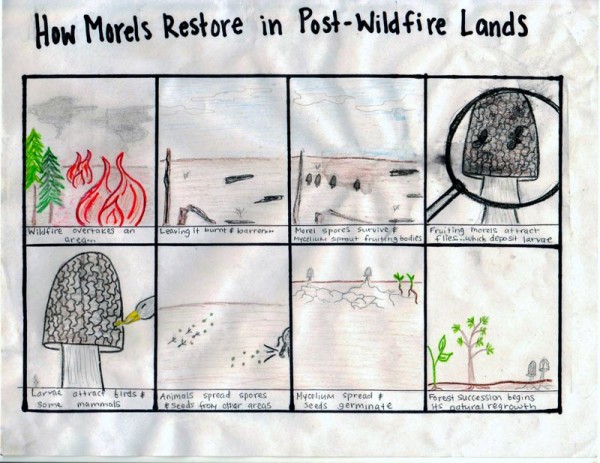

As many fungi lovers may know, Morels crop up after wildfires, and will spread far and wide in places that look barren. As these edible delicacies grow, they act as pioneers of biodiversity; along with spores, they release a smell that attracts all manner of invertebrates and some mammals. Invertebrates like flies then leave their larval young in the fleshy mushroom bodies, which attracts birds.

Then, like pollinators such as bees, animals who come in contact with the Morels are dusted with spores, and disperse them all over the area. And voila, through the powers of natural mycorestoration, the forest has begun a portion of its post-fire restoration leading to a return of biodiversity and an ecosystem with the resources to sustain those species.

Our own little burn area, the Lake Fire

Fungi that can Filter

The amount of mycelium (those root-like structures of fungi) in the soil is amazing. These mycelial cells connect almost like neurons in our brains, creating a thick underground network. In many parts of the world, a teaspoonful of soil can be infused with an entire mile’s worth of mycelial cells. Neat information in and of itself, right?

Oyster mushroom mycelia

The real question though, is how can mycelium help us with water pollution? Well, as mentioned previously, mycelial cells create a thick net. That net alone can catch many particles such as silt, microscopic organisms, and pollutants. And in some cases, that net even consumes and digests those particles, cleaning that water right up.

Back in my home state of Washington, in a town called Sequim, a laboratory has done more extensive research on the topic. Battelle Marine Sciences Laboratory has done research that has found that Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) not only can filter organic silt and other particles from water, but it can actually clean up our very human-made messes, such as oil. 1

Back in my home state of Washington, in a town called Sequim, a laboratory has done more extensive research on the topic. Battelle Marine Sciences Laboratory has done research that has found that Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) not only can filter organic silt and other particles from water, but it can actually clean up our very human-made messes, such as oil. 1

Mycofiltration: a sub-category of myorestoration in which people harness mycelium to filter out microorganisms, pollutants, and silt.

Oysters on Contaminated Soil

In another Washington town, Bellingham, (where I lived for the past four years), the Battelle Lab did some poking around in an old truck maintenance yard which had soil with extremely high levels of oil and gasoline contamination. They decided to set up an experiment to compare bacterial treatments and fungi treatments.

Oysters with drastically reduced toxicity levels. Credit Susan Thomas.

After a few weeks, those Oyster

Mushrooms’ spores, which had been put into woodchips and layered into the contaminated soil, reduced the oil particulates by amazing amounts! The mushrooms that sprouted out of the piles were unsafe to consume, but amazingly enough, did not even contain petroleum.

That means the mushrooms were able to intake and completely digest and remediate the majority of the toxins.

Plus, after a few months of fungi growth, the soil lost its dark, diesel appearance; lost its awful odor; and was attracting birds, insects, and growing plants.

Now, that same research, along with the research from other similar experiments has fueled the moves towards using fungi to fix ocean oil spills. Paul Stamets writes about his testing of “MycoBooms,” in conjunction with the work done by the Battelle Lab. It seems that Oyster Mushrooms show incredible promise, as they are tolerant to saltwater, can remediate toxins such as oil, and can live in floating “MycoBooms” (straw with Oyster Mushroom spores, encased in hemp tubes).

Now, that same research, along with the research from other similar experiments has fueled the moves towards using fungi to fix ocean oil spills. Paul Stamets writes about his testing of “MycoBooms,” in conjunction with the work done by the Battelle Lab. It seems that Oyster Mushrooms show incredible promise, as they are tolerant to saltwater, can remediate toxins such as oil, and can live in floating “MycoBooms” (straw with Oyster Mushroom spores, encased in hemp tubes).

Is this the solution to large oil spills like the BP/Deepwater Horizon spill? Perhaps not right now; however, this sort of mycoremediation could lead to incredible breakthroughs in how we can use the natural world of fungi for the betterment of the Earth.

Mycoremediation: using fungi to degrade or sequester toxic contaminants in the environment.

On their own, fungi are fixing ecological problems one step at a time. But as humans, if we can learn more about this mysterious kingdom, we can lend a hand in setting the stage for some big changes. We’ll get the ball rolling, and the little world of mycelium can do the rest to make for a happier, healthier planet.

Chehala and some decomposers in our forest taking on a downed black oak.

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

- Stamets, P. (2005). Mycelium running: How mushrooms can help save the world. Berkeley, Calif.: Ten Speed Press. ↩

Comments are closed.