I want you to picture a mountain in your mind’s eye. It’s what our students see the moment they step off the bus here at High Trails. From then on, their imaginations (and questions) are inspired by this majestic scenery around them. Soaring peaks, towering treetops, crystal clear lakes and streams, and… bears?!

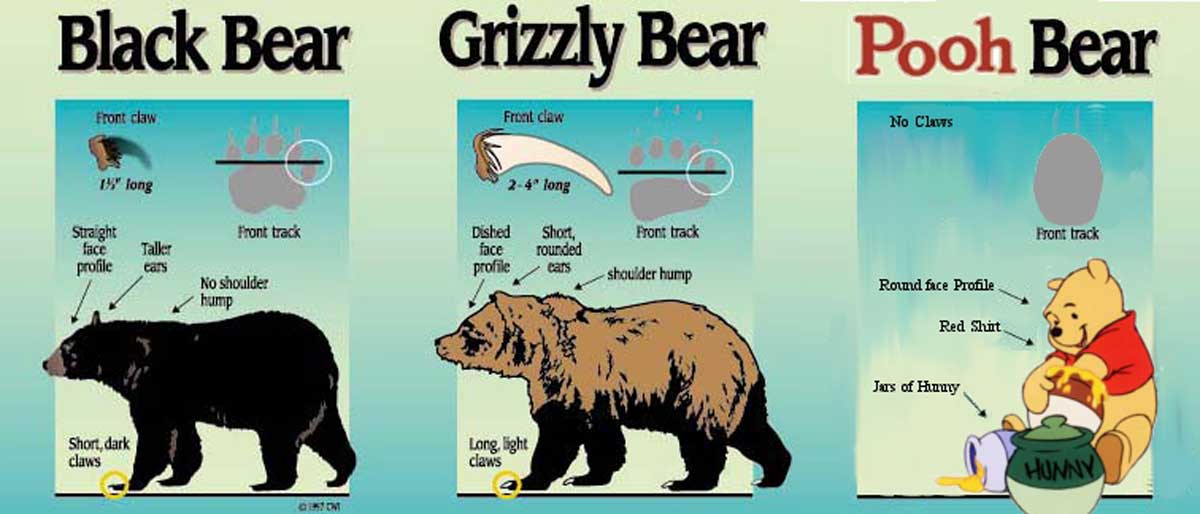

Yes, bears do live here in the San Bernardino National Forest. Black bears, to be exact.

They’re as much a part of the mountains as Ponderosa pines, or Steller’s jays, or anything else here is. Yet, whenever Black bears inevitably come up on our Team Discovery Hike, my students seem especially in awe of them. Perhaps it’s because they are so secretive – for such a large creature, they rarely appear in front of us or anyone else. Perhaps it’s because of their reputation – they are often seen as fearsome and powerful, deserving of our respect and demanding a wide berth. Whatever the reason, I love talking about Black bears with students because many of them have never had the opportunity to see something so “wild” before, especially in their native habitat.

But wait… are black bears native to southern California?

This is where the already-wide eyes in front of me get even wider. As it turns out, they’re not, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife 1. Black bears were introduced here in the 1930s to make up for the absence of Brown bears, which were the original bears to inhabit these mountains.

Nods of understanding usually follow this revelation. Most weeks, one of my students has a picture of the California state flag on their backpack, or their hat, or somewhere else; now is the time I hear a voice excitedly shout: “There’s a Brown bear on our flag!” Indeed, there is, which of course begs the question: What happened to them? We briefly touch on this during our first day together, and the short story is, well, grizzly. Settlers hunted them to the point of extinction over a century ago, as Johnson 2 describes; out of desire for food; out of desire for space; out of desire for protection; and out of a desire simply to see them gone. It’s a cautionary tale about the consequences of human activities and how they sometimes cannot be reversed. Except, in this case – much to my students’ intrigue – it might be possible to do so.

Nods of understanding usually follow this revelation. Most weeks, one of my students has a picture of the California state flag on their backpack, or their hat, or somewhere else; now is the time I hear a voice excitedly shout: “There’s a Brown bear on our flag!” Indeed, there is, which of course begs the question: What happened to them? We briefly touch on this during our first day together, and the short story is, well, grizzly. Settlers hunted them to the point of extinction over a century ago, as Johnson 2 describes; out of desire for food; out of desire for space; out of desire for protection; and out of a desire simply to see them gone. It’s a cautionary tale about the consequences of human activities and how they sometimes cannot be reversed. Except, in this case – much to my students’ intrigue – it might be possible to do so.

Brown bears, a.k.a. Grizzly bears, may yet call California home again, if the efforts of several wildlife conservationists are successful.

The discussion usually ends on this hopeful note, but more than once I’ve had a curious student ask me afterwards: Why would we want to bring Brown bears back when we have Black bears now? That is, admittedly, an excellent question, and one I wasn’t completely confident answering. After doing some research on my own, things became a little clearer. Because the Brown bear is still protected by the Endangered Species Act, many have argued that it should be re-introduced throughout its historic range in order to ensure its continued survival and recovery 3. This could be an effective way to combat slow population growth, habitat changes due to global warming, and more. Scientists are also quick to point out that this is not just a nostalgia trip, either: Brown bears could positively impact ecosystem factors such as biodiversity and soil quality. They could also provide valuable services such as prey population control and nutrient transport.

With so much support behind their possible return to California, why aren’t Brown Bears back in California already?

In the century or so that Brown bears have been gone, a lot has changed. The state of California now boasts a population of almost 40 million people. More people not only mean fewer bears, it means less habitat for bears as well. Brown bears traditionally favored habitat along the coast, which has been extensively developed for human use – to the point that some conservationists see a return as impossible, however desirable it may be 4. Many residents are also understandably nervous at the idea of seeing them again, as they are known for their notoriously poor relations with humans. The discussion surrounding Brown bear reintroduction is still ongoing, and could take many years before a decision is reached.

In the meantime, though, I (and many others, I imagine) still find inspiration in the possibility of a Brown bear return.

It shows that even though we humans can sometimes make mistakes, we are capable of righting them as well. Every week, I tell my students the story of the Brown bears that once called these mountains home. Imagine if I could change the ending of that story. Imagine if I could tell them that, some day, Brown bears will come back. Wouldn’t that be something? It might not be as impossible as you think.

It shows that even though we humans can sometimes make mistakes, we are capable of righting them as well. Every week, I tell my students the story of the Brown bears that once called these mountains home. Imagine if I could change the ending of that story. Imagine if I could tell them that, some day, Brown bears will come back. Wouldn’t that be something? It might not be as impossible as you think.

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

- California Department of Fish and Wildlife. (n.d.). Black bear population information. Retrieved from: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Mammals/Black-Bear/Population ↩

- Johnson, B. (2014). Great grizzly bear hunt in Santa Paula backcountry reaps state flag icon, tall tales. Ventura County Star. Retrieved from: http://archive.vcstar.com/news/special/outdoors/great-grizzly-bear-hunt-in-santa-paula-backcountry-reaps-state-flag-icon-tall-tales-ep-543959500-351277721.html ↩

- Woody, T. (2014). A new move to bring the grizzly bear back to California. TakePart. Retrieved from: http://www.takepart.com/article/2014/06/20/new-move-bring-back-grizzly-bear-california ↩

- Cart, J. (2014). California: The next grizzly habitat? Some want to see it happen. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from: http://www.latimes.com/local/la-me-adv-california-grizzly-20140803-story.html ↩

Comments are closed.