Here at High Trails we live and work in the San Bernardino Mountains. While beautiful and incredibly diverse, our local mountains pale in size, height, and snowpack when you compare them to the vastness of the Sierra Nevada in central California. Mountaineers and the adventurous backpacker flock to the Sierra Nevada year round to bag peaks like Mount Whitney, climb new routes, ski in the backcountry, or just to backpack along the many trails such as the High Sierra Trail and John Muir Trail.

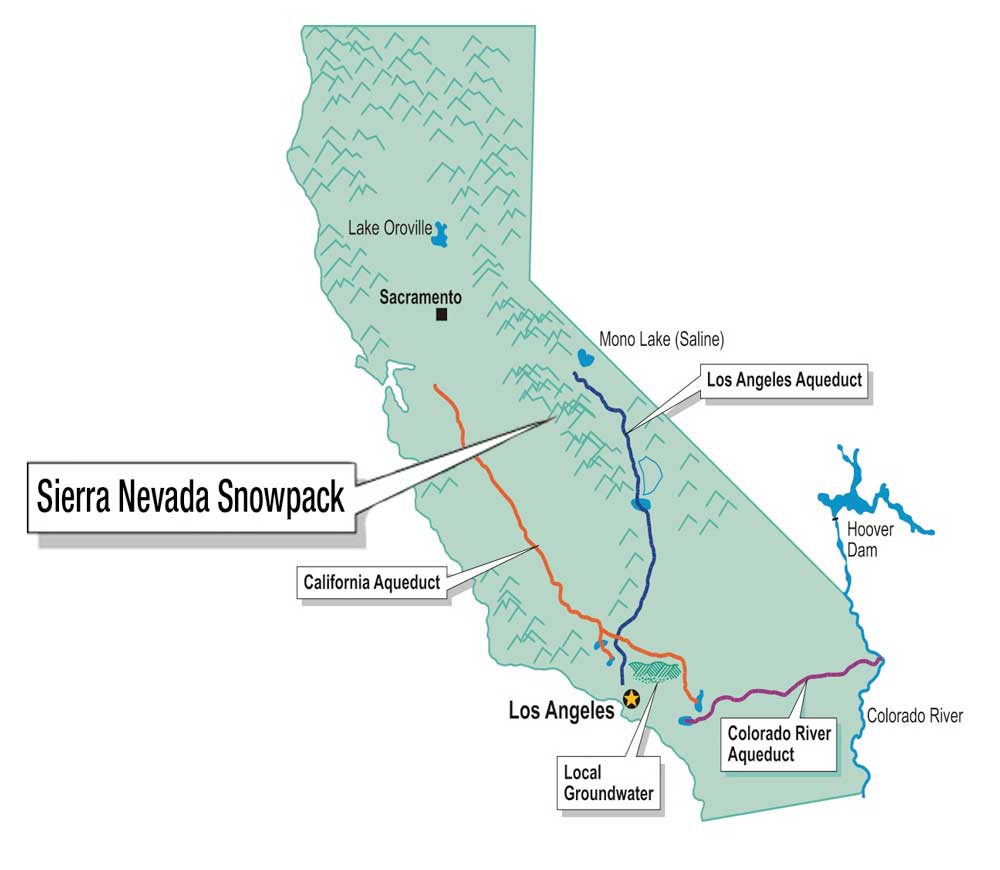

Not only do the Sierra Nevada provide peace and solace for the adventurous soul but they also provide almost half of the water for the San Francisco Bay Area and 30% of the water for the Los Angeles area! 1 The water supplied by the Sierra Nevada comes from winter snowpack, which is so important, in fact, that the California Department of Water Resources has researchers hike out and make measurements all winter. 2 Here are some good class facts about the Sierra Nevada snowpack and the water that comes from this massive mountain range.

Why do the Sierra Nevada mountains receive so much snow?

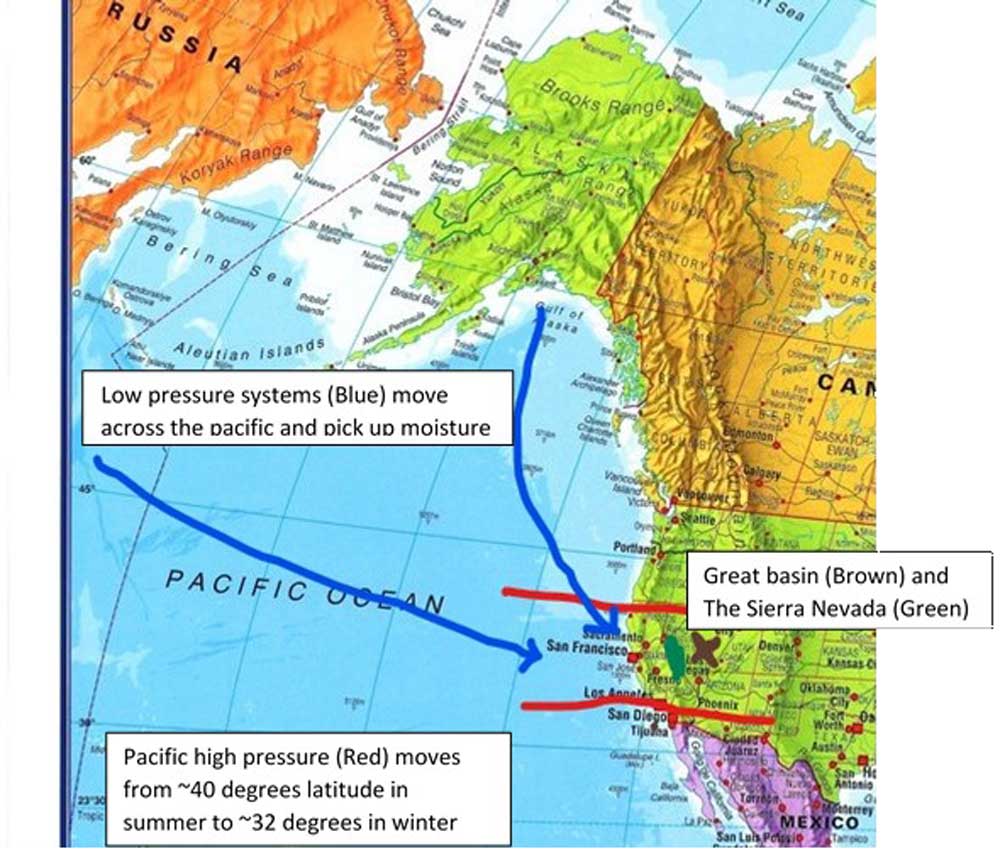

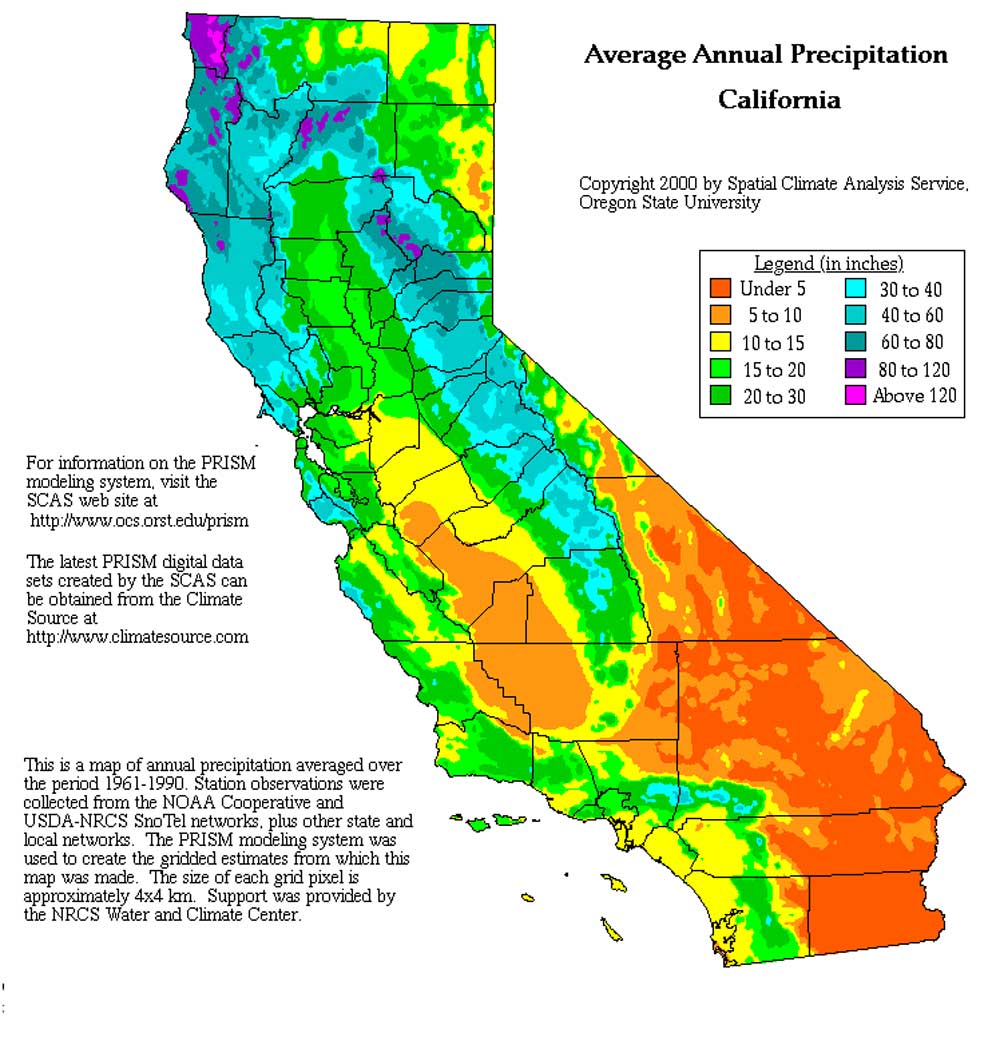

Typically, low pressure weather systems gather moisture which is then released when colliding with a high pressure system. Precipitation is also wrung out of clouds when they collide with mountains. In the winter time, the Pacific high pressure system moves from northern California (about 40*) south to the San Diego area (about 32*).

This allows low pressure systems to travel from the Gulf of Alaska southeast across the Pacific (picking up moisture as it travels) until they collide with the mountains. Additionally, high pressure systems over the Great Basin can redirect pacific storms up into the mountains.

The combined effects of wind current direction and the placement of the Sierra Nevada in relation to winter high pressure and low pressure systems allow these mountains to receive such high amounts of snow.

Where does the Sierra Snowpack go?

California is a huge center for agriculture and has a large population of 34.5 million people. But much of it is very dry and receives little natural precipitation. The Los Angeles area gets its water from the 90-mile-long Owens River Valley which lies to the east of the Sierra crest and is flanked on the other side by the very dry White Mountains.

The Owens River Valley doesn’t receive much water from storms in the valley itself; by the time clouds get there just about all the precipitation has been wrung out due to rain shadow. Instead, it used to get snow melt through streams from the Sierra Crest to Mono Lake (to the east of Yosemite National Park) and Owens Lake (to the southeast of Sequoia National Park). In 1913, the City of L.A. built an aqueduct that redirected water that would travel to Owens Lake south to the city. In 1941, this water project was also connected to Mono Lake. This aqueduct system carries 400,000 acre-feet of water to Los Angeles every year. 3

This diversion of water for human uses has a heavy impact on local environments that also depends on the water sources to survive. In the late 20th century, a law suit forced Los Angeles to increase the supply of water to the dwindling Mono Lake as fish and riparian habitat were being destroyed by the diversion of water.

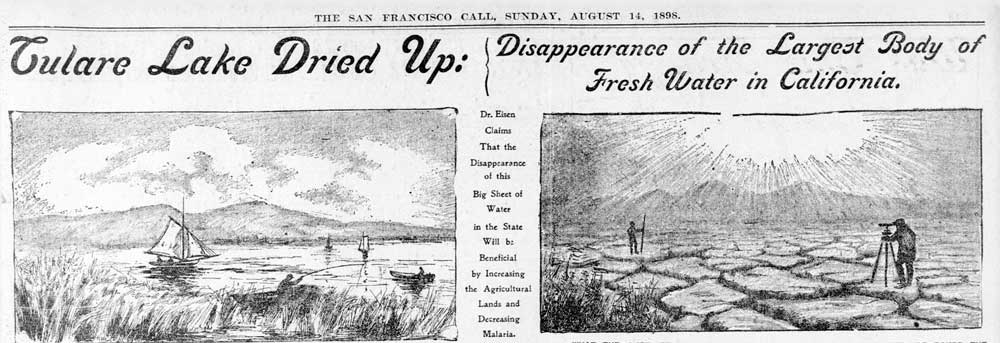

To the west, the Tule, Kings, and Kaweah rivers used to terminate in Tulare Lake. Tulare Lake no longer exists as the water from these rivers has been diverted to feed agricultural needs in the Central Valley. Dams and aqueducts have been installed into most of the Sierra Nevada river canyons to capture the yearly snowfall for human usage. Normally, the snowmelt feeds the wetlands and riparian areas of the state of California, however many of these habitats are now dried up, which has detrimental effects on native species.

To the west, the Tule, Kings, and Kaweah rivers used to terminate in Tulare Lake. Tulare Lake no longer exists as the water from these rivers has been diverted to feed agricultural needs in the Central Valley. Dams and aqueducts have been installed into most of the Sierra Nevada river canyons to capture the yearly snowfall for human usage. Normally, the snowmelt feeds the wetlands and riparian areas of the state of California, however many of these habitats are now dried up, which has detrimental effects on native species.

For both humans and animals, who knew how important snow is? Not only do we love to play in it, but it provides the most important resource for all living things. As climate change causes yearly snowpack to diminish, it will be ever important to understand where our water comes from.

For both humans and animals, who knew how important snow is? Not only do we love to play in it, but it provides the most important resource for all living things. As climate change causes yearly snowpack to diminish, it will be ever important to understand where our water comes from.

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

Comments are closed.