We teach both primarily 5th and 6th grade students. Is there really that big a difference in that one year of life that affects how teachers teach and students learn?

Recently, I had the privilege to observe a 5th & 6th grade classroom in Lucerne Valley, a desert town on the northern side of the San Bernardino Mountains. Lucerne Valley Elementary School had, within the past two years, implemented a policy of combining 5th and 6th graders for certain academic classes like English Language Arts, Math, and even for their recess time. However, science and social studies were still separated by grade.

Recently, I had the privilege to observe a 5th & 6th grade classroom in Lucerne Valley, a desert town on the northern side of the San Bernardino Mountains. Lucerne Valley Elementary School had, within the past two years, implemented a policy of combining 5th and 6th graders for certain academic classes like English Language Arts, Math, and even for their recess time. However, science and social studies were still separated by grade.

Homeroom was a combination of 5th & 6th graders, and in addition to the traditional requirements of homeroom – listening to announcements, taking attendance – included reviewing a school campaign on fairness. In comparison to my work in Outdoor Education, this review and reflection on “fairness” with school reminded me of Full Value Contracts that is often a facet of experiential outdoor education.

Homeroom was a combination of 5th & 6th graders, and in addition to the traditional requirements of homeroom – listening to announcements, taking attendance – included reviewing a school campaign on fairness. In comparison to my work in Outdoor Education, this review and reflection on “fairness” with school reminded me of Full Value Contracts that is often a facet of experiential outdoor education.

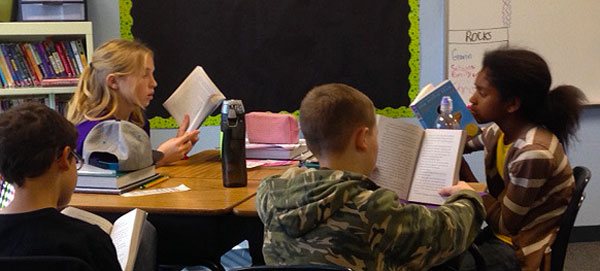

The first class I observed was English Language Arts (ELA). Like homeroom, it was a combination of 5th & 6th graders.

Spelling test review was done in a large group. The range of ages participating in it and spelling curriculum is something that follows a common thread with this age group: they enjoy memorizing how to spell and use difficult words and the readiness to learn more dictionary skills (dictionary use was allowed to preview upcoming spelling and preview upcoming story vocabulary).

There was also some time during class for independent reading and time for group reading a common book that they had been reading through the week. All of this ELA work reflects the cognitive growth of these two age groups – receptive to learning and eager to develop new skills rather than review or improve previous work.

However, at some point during the morning, the class began a tangential discussion about the school’s “lawn” – a courtyard of grass once exclusively for 6th graders, but had in this school year, been opened to 5th graders. 6th graders in the class cried defensively about the lack of fairness: in their world it had always been the 6th grade lawn, reserved for the oldest students and something they looked forward to as an earned reward for making it to 6th grade. The 5th graders did not call to arms for “the lawn,” but rather the teacher asked a few questions to the class about fairness, sharing, and the perception of loss in a zero-sum situation (“Are you really losing ‘the lawn’ by sharing with just a few more students?”).

6th graders in the class cried defensively about the lack of fairness: in their world it had always been the 6th grade lawn, reserved for the oldest student.

The transition from a mutual learning environment with reading, writing, and spelling into the deeply entrenched defenses of Us versus Them when it came to distribution of resources stood out as another strong example of the developmental differences that occur between the ages of 10 and 12.

So what is the difference between 5th & 6th graders? Why can they share a classroom but get defensive about things like “the lawn”? What is going on in the minds of 5th versus 6th graders? What happens in these two years that causes such clear cut examples of different behaviors and reactions to educational settings?

5th Grade

Ten year olds need a great deal of physical activity as their large muscles are developing. They are receptive learners and very good at memorization. They are generally satisfied with their own abilities and enjoy being noticed and rewarded for their efforts. Their social-emotional behavior is basically cooperative and conducive to group activity – they are eager to “go with the flow” of directions for a group activity.

6th Grade

Eleven year olds are restless and very energetic. This is the beginning of puberty and adolescence, so they become more self-absorbed and self conscious as the bodies they were once so comfortable with are changing on them. They are seeking to grow up and imitate adult language and take on perceived adult style tasks like research, interviewing, and are interested in putting themselves in the world of history and current events. However, they also desire to test and explore the limits and rules, and enjoy the challenge of competition.

While understanding the development of these two ages is helpful in the classroom, I want to look at how this plays out when we work with both age groups at High Trails. Let’s look at how the age groups engage in the ever popular High Trails incentive – the bead.

5th Graders and High Trails Beads

From an instructor’s point of view, the ten year old will be the smallest behavioral issue in your group, they will be eager to follow instructions, listen, and remain part of the group (which is why isolating a student from the group, in say a “time out,” is such an effective consequence at this age.) They will be eager to learn and memorize new vocabulary; they will be dependable in following instructions and helpful in group activities.

From an instructor’s point of view, the ten year old will be the smallest behavioral issue in your group, they will be eager to follow instructions, listen, and remain part of the group (which is why isolating a student from the group, in say a “time out,” is such an effective consequence at this age.) They will be eager to learn and memorize new vocabulary; they will be dependable in following instructions and helpful in group activities.

However, regarding the earning of their bead for a class or activity, they will struggle with higher-level questions applying their new knowledge to their lives and will look to demonstrate their knowledge by reciting new vocabulary words and definitions. Also, as they desire that recognition for their actions, they will sincerely ask for a bead with every task set before them. The instructor will be eager to give them a bead for their good behavior and reception to new information from class, but may grow tired of the chronic “Do I get a bead for this?!”

6th Graders and High Trails Beads

For the eleven year old, they may ask at various times deep level, if off-topic, questions that intertwine themselves in current events and information. They will listen a little less to you as you lecture, but engage a lot more if you hand out guide books, pamphlets, pictures, and props. They are going to push the rules to explore how far they can go – they will pick up sticks, walk on logs, and try to walk off the trails as they follow the group.

When it comes time to earn the bead, the instructor can ask deeper level questions beyond vocabulary, allowing the student to connect and synthesize material to their lives and the bigger picture of the world. The bead transitions from a reward recognizing their accomplishments to a status symbol, a bead is something personal and can be compared to the collections of others.

Not earning a bead won’t make the student upset with their faults but more self conscious that others have something they don’t.

Eleven year olds won’t chronically ask, “Do I get a bead for this?” but the instructor may hesitate in giving the bead, not because of the student’s lack of knowledge, but because of the student’s possible boundary testing throughout the day (however natural a part of their development this may be).

Sum It Up

Observing the classroom, the cooperation in learning during ELA but the division over perception of fairness and self-perception over using “the lawn” reinforced my understanding of the stark differences in the close ages we work with here at High Trails. Seeing the class made me go back to understanding and reviewing adolescent development and the dramatic changes that occur from age 10 to 11. Knowing how different these age groups can be allows us to adjust our teaching and management as the schools and grades that attend High Trails change from week to week.

I could not have written this without the help of Mrs. Leah Paddack at Lucerne Valley Elementary, and so many, many thanks for allowing me to observe her class. Also the best resource I have used for understanding and reviewing child development, something I referred to in writing this blog, is Yardsticks: Children in the Classroom Ages 4-14 by Chip Wood, a practical guide summarizing stages of development in children for teachers.

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

Comments are closed.