Exploring the Research on How Fire is Changing the West

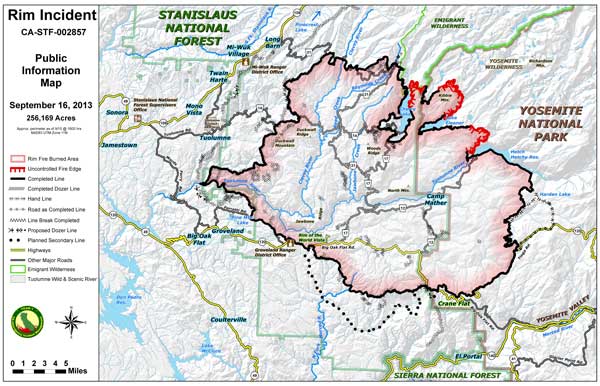

Late summer of 2013 brought the most destructive day of California’s Rim Fire, when wind and prolonged drought conditions created an inferno that transformed 30,000 acres of dense conifers in Tuolomne County near Yosemite National Park into a moonscape.

Ignited on August 17, 2013, from an illegal campfire, the Rim Fire scorched 400-square-miles of the Stanislaus National Forest, affecting 25 watersheds that supply drinking water to millions of Californians. It later spread into Yosemite National Park, an icon of American conservation.

However, fires are a natural and crucial part of forest ecosystems and new growth can already be seen sprouting from the ashen soil in the blackened canyons of Tuolomne County.

However, fires are a natural and crucial part of forest ecosystems and new growth can already be seen sprouting from the ashen soil in the blackened canyons of Tuolomne County.

“Next spring we’ll see a lot of wildflowers and plants that haven’t been seen around here for a long, long time. In 20 years, we’ll see something really nice. But it will take 200 years at least for it to grow back the way it was,” said Sean Collins of the South Central Sierra Incident Command Team as he examined tiny patches of greenery unfurling their leaves. 1

Many people across the West await the arrival of the summer months with dread, wearily expecting the onslaught of fires as the tinderbox-like conditions of their surrounding landscapes ignite. The summer of 2013 transformed Yosemite into a blazing conflagration that smoldered until October, affecting the water and air quality of Northern California and creating a months-long health problem.

In the summer of 2012 the foothills just west of Colorado Springs exploded into flame, transforming the landscape beneath beautiful Pikes Peak into Armageddon and choking the Front Range with smoke with the Waldo Canyon Fire. In the last twenty years, the increasingly destructive phenomenon of wildfires has changed the face of the West and the catastrophic element of these fires may be the new normal.

In National Geographic’s article entitled “Why Big, Intense Wildfires are the New Normal,” Melody Kramer explores and synthesizes the facts surrounding the wildfires that rage rampant across the West each and every summer.

In National Geographic’s article entitled “Why Big, Intense Wildfires are the New Normal,” Melody Kramer explores and synthesizes the facts surrounding the wildfires that rage rampant across the West each and every summer.

Destruction of property, homes and communities, exorbitant amounts of debt, the safety of residents and firefighters alike, habitat loss, poor air quality, and loss of wilderness lands are only some of the major effects occurring each summer from these destructive blazes.

“In the West, there has been a nearly fourfold increase in large wildfires in recent decades, with greater fire frequency, longer fire durations, and longer wildfire seasons,” cited the U.S. Global Change Research Program’s report on the impact of climate change across the country in 2009. 2

“In the West, there has been a nearly fourfold increase in large wildfires in recent decades, with greater fire frequency, longer fire durations, and longer wildfire seasons,” cited the U.S. Global Change Research Program’s report on the impact of climate change across the country in 2009. 2

What is fueling these destructive fires?

Severe drought, increased amounts of dried-out vegetation and higher global temperatures coupled with larger populations of people living in forested and mountainous areas have created frequent and firebomb-like wildfires that scorch the West every summer. Additionally, Western forests have been affected by Forest Service managing policies that have now been called into question. Prior to 1970, the Forest Service utilized fire suppression, or in other words, they prevented fires from burning in forests at all, which allowed dried-up brush to build up the understory. The sheer amount of dry vegetation in our forests combined with severe drought conditions have caused the West’s forests to resemble tinderboxes ready to ignite.

“The great irony of the decades of aggressive fire suppression is that in many parts of the West it has made fires larger and more destructive,” 3

In 2007 the Butler 2 Fire forced us to move off the Camp Whittle site.

For example, fires have historically been an integral part of maintaining healthy Ponderosa Pine forests by removing undergrowth but sparing larger, thicker-barked trees. However, suppressing low-intensity, cleansing fires allow the underbrush to accumulate into copious amounts of fuel for these fires, which then become the destructive fires of today.

The question is no longer why these fires are occurring. That answer has been illuminated by numerous studies, which prove that despite the fact that wildfires have always been a natural part of forest ecosystems, the catastrophic element of today’s wildfires happen because of climate change. According to the National Wildlife Federation “The frequency of large wildfires and the total area burned have been steadily increasing in the Western United States, with global warming being a major contributing factor”. 4

What can we do to help prevent/ live with these fires?

As more and more people move to the West, wanting to live as close to the mountains or forests as possible, populations that border wildlands are growing increasingly fast. These regions, in which cities jut up to the very edge of forests or mountains, have been deemed the Wildland-Urban Interface ( WUI for short). “The number of housing units within half a mile of a national forest, for instance, grew from 484,000 in 1940 to 1.8 million in 2000,” 5, or tripled. Some 70,000 communities in the U.S. are at high to moderate risk from “uncharacteristically large wildfires,” estimates the U.S. Forest Service. 6

While the desire to live close to the mountains and natural forests is understandable (…many staff members at High Trails will say that a desire to live in the woods is one of the primary reasons they came to work here), it’s important to realize that the prevalence of populated WUIs puts both firefighters and communities at risk. While small burns could be beneficial to these wildland areas, clearing out dry brush, the presence of man-made structures in the interface create an obligation for firefighters to put out the fires.

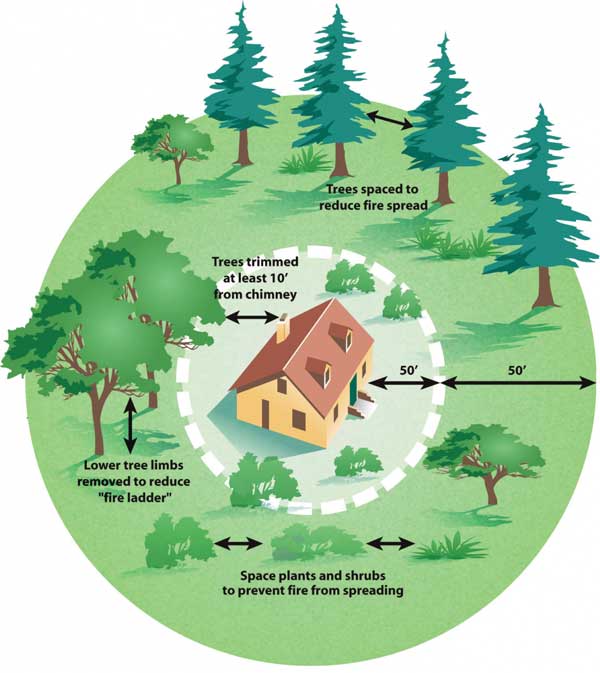

It is also important to recognize that with the privilege of living by the mountains or by the forest comes the responsibility of taking the measures to protect yourself and your home. Laws mandating personal fire mitigation have passed in some Western states in which residents must keep their home clear from flammable underbrush such as dry pine needles, branches, and other kindling-like vegetation.

It is also important to recognize that with the privilege of living by the mountains or by the forest comes the responsibility of taking the measures to protect yourself and your home. Laws mandating personal fire mitigation have passed in some Western states in which residents must keep their home clear from flammable underbrush such as dry pine needles, branches, and other kindling-like vegetation.

“There are some counties in Arizona and New Mexico and Colorado that compel residents to take mitigation measures—like building structures that are made of fire-resistant materials—and others that have done nothing at all,” says Lloyd Burton, a University of Denver professor who studies environmental and disaster management law and policy. 7

Back At High Trails

We at High Trails feel lucky to live up in the San Bernardino Mountains. We feel lucky to get to show off our beautiful cedar trees and Ponderosa Pines to students from all over Southern California. We feel lucky to see the Milky Way and the moon each and every night. However, I always take the students in my field group to an area we’ve dubbed “Burnt Flats” for the prevalence of trees with burnt bark and old, disintegrating logs from trees that fell during a fire nearly four decades ago in the 1970s.

We at High Trails feel lucky to live up in the San Bernardino Mountains. We feel lucky to get to show off our beautiful cedar trees and Ponderosa Pines to students from all over Southern California. We feel lucky to see the Milky Way and the moon each and every night. However, I always take the students in my field group to an area we’ve dubbed “Burnt Flats” for the prevalence of trees with burnt bark and old, disintegrating logs from trees that fell during a fire nearly four decades ago in the 1970s.

Sometimes the students seem surprised that the area still shows such evidence of a fire that occurred decades before they were born. But that’s the point I try to bring home for them. Fire has a lasting impact. Ecosystems do not grow back right away from a fire that churns through an area. Fires are a natural and important part of any ecosystem, but the fires of the past are not the fires of today. Today’s fires carry a destruction with them that would have seemed unimaginable back in the 1970s. And as residents of both the forest and the mountains, we must ask ourselves what can we do to help.

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

- Cone, Tracie. “Following Yosemite Rim Fire, Regeneration Begins.” 27 September 2013.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/28/yosemite-rim-fire-regeneration_n_4007885.html. ↩ - http://library.globalchange.gov/products/assessments/2009-national-climate-assessment/2009-global-climate-change-impacts-in-the-united-states. ↩

- Kenworthy, Tom. “Western Wildfires Getting Worse in a Warming World” 9 July 2012.

http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/green/news/2012/07/09/11889/western-wildfires-getting-worse-in-a-warming-world/. ↩ - http://www.nwf.org/Wildlife/Threats-to-Wildlife/Global-Warming/Global-Warming-is-Causing-Extreme-Weather/Wildfires.aspx ↩

- Kenworthy, Tom. “Western Wildfires Getting Worse in a Warming World” 9 July 2012.

http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/green/news/2012/07/09/11889/western-wildfires-getting-worse-in-a-warming-world/. ↩ - http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/08/130827-wildfires-yosemite-fire-firefighters-vegetation-hotshots-california-drought/ ↩

- http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/08/130827-wildfires-yosemite-fire-firefighters-vegetation-hotshots-california-drought/ ↩

Comments are closed.