Leading students into the forest at night, though exciting for me as an instructor, proves to be a great test of courage for most 5th and 6th graders. When I ask students to, “Please turn off your flashlights.” I am immediately contested with 14 voices pleading against my request.

When they finally give in and click their flashlights off, we are all drowned in darkness. But only for a few moments until our eyes begin to adjust to the limited light.

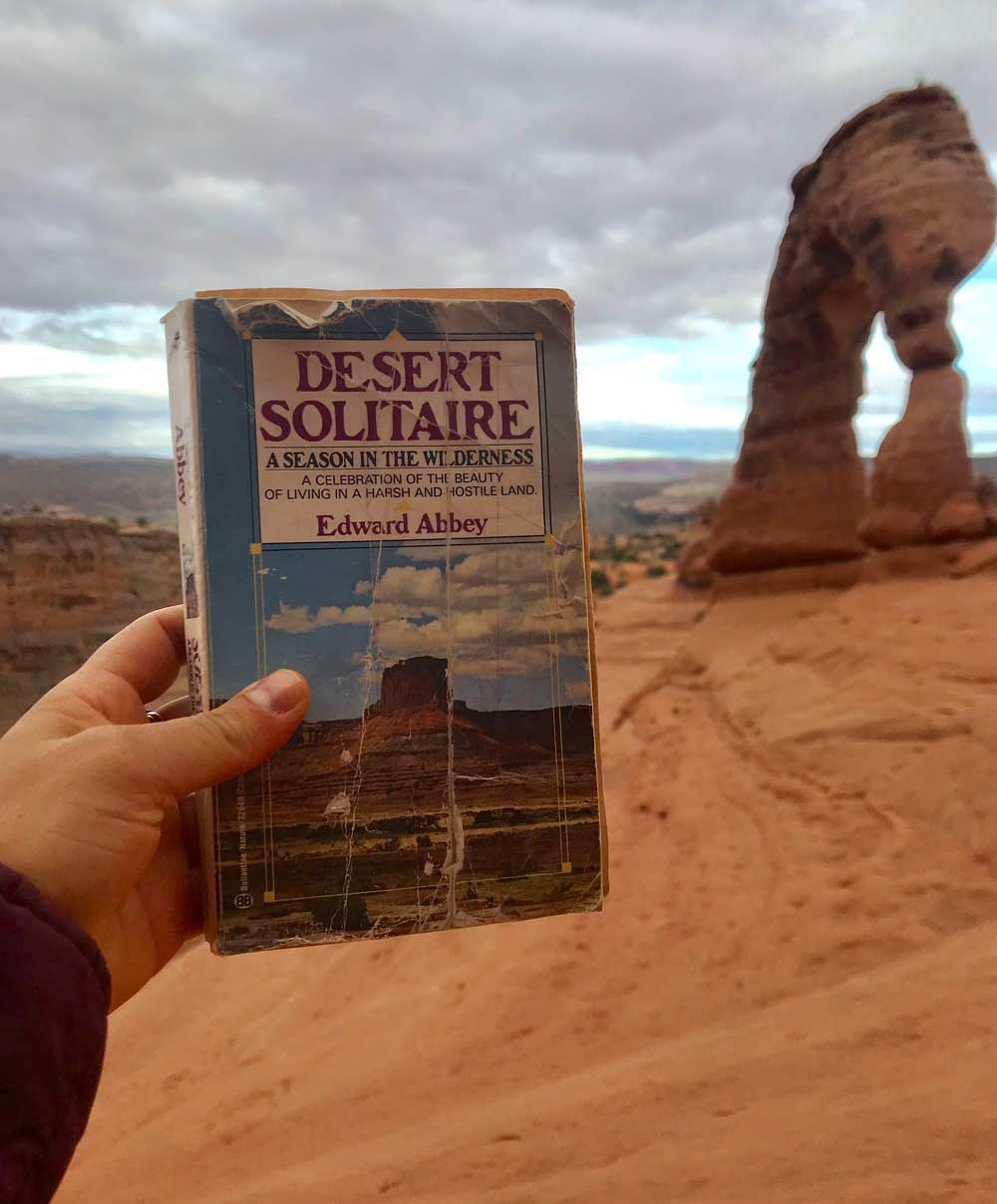

Then, wrapping up our Nocturnal Nation class (all about animals of the night), I read a passage from Edward Abbey’s book Desert Solitaire: a Season in the Wilderness, before enacting a silent, individual walk through the forest. The passage begins with, “There’s another disadvantage to the flashlight: like many other mechanical gadgets it tends to separate a man from the world around him,” and goes on to describe a sense of feeling comforted and welcomed by wilderness even in the darkness.

When Abbey wrote his book, in the mid 1950s, he was the sole park ranger of what was then Arches National Monument in Moab, Utah, later becoming a National Park in 1971 under Nixon’s Presidency 1. Not too long ago Arches National Park was undeveloped with a true sense of wilderness, not yet lost to the hordes of tourists visiting it each year. His famous book, Desert Solitaire, talks a great deal about reconciling his internal dilemma of protecting the park while still making wild spaces available for public enjoyment and education.

When Abbey wrote his book, in the mid 1950s, he was the sole park ranger of what was then Arches National Monument in Moab, Utah, later becoming a National Park in 1971 under Nixon’s Presidency 1. Not too long ago Arches National Park was undeveloped with a true sense of wilderness, not yet lost to the hordes of tourists visiting it each year. His famous book, Desert Solitaire, talks a great deal about reconciling his internal dilemma of protecting the park while still making wild spaces available for public enjoyment and education.

A read well suited for visual learners, the book is full of beautiful imagery describing the desert landscape including its variety of flora, fauna, water systems, geology and more. The book emphasizes the importance of all natural systems, which make up the larger ecosystem surrounding the Arches. The interconnectedness of the natural world is a theme we also work hard to relay to all students at High Trails.

Desert Solitaire serves as both a natural history of Arches as well as a commentary on industrial tourism.

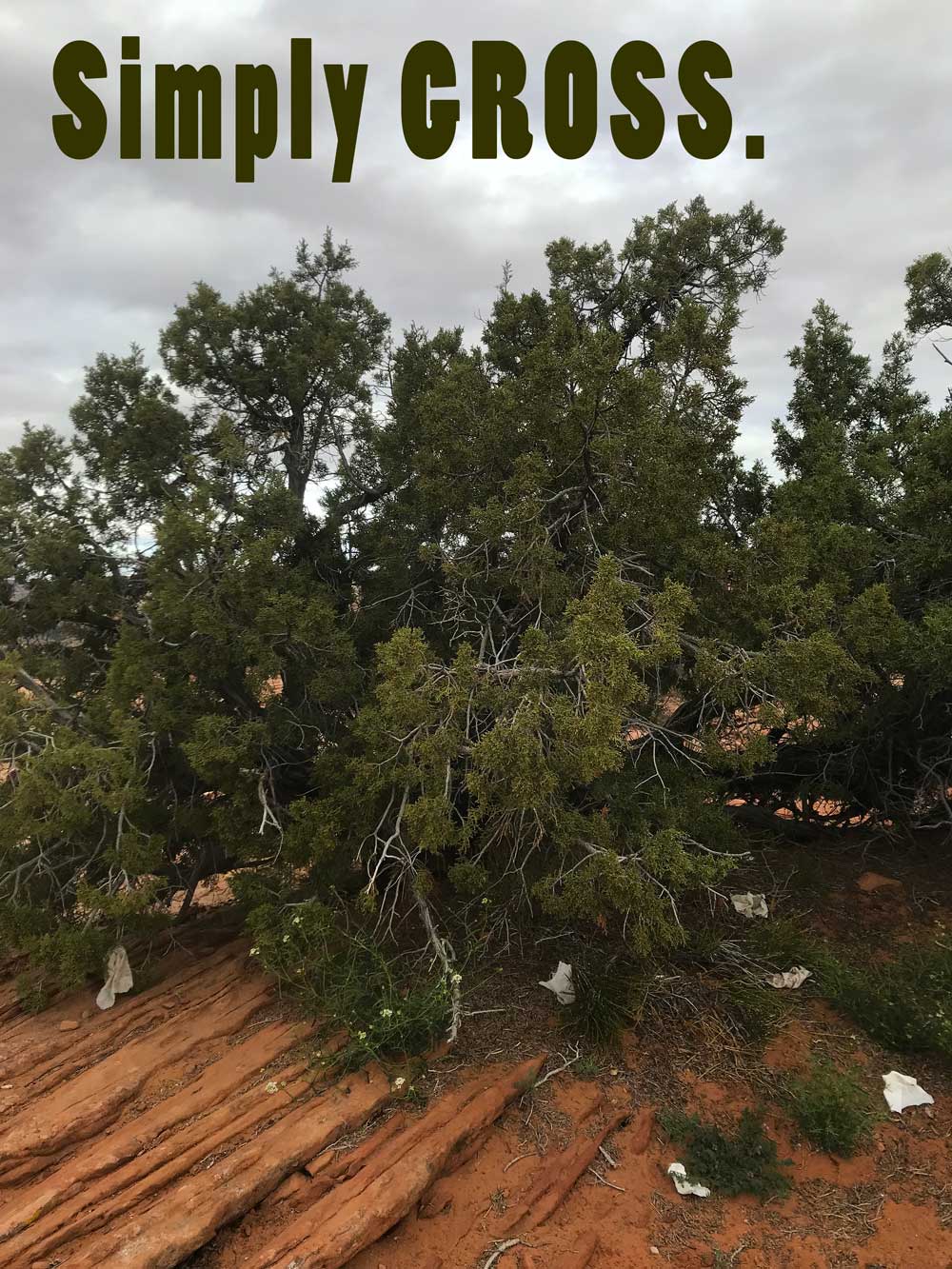

During the mid 1900’s, the Department of Interior worked with local ranchers to hunt, poison, and sterilize coyotes and mountain lions among other predators with the goal of decreasing the number of lambs killed each spring. Abbey reported never seeing a single mountain lion or coyote during his two seasons in the park, proving the Department of Interior’s effect. In perhaps a less severe example of human interference with nature, Abbey described a weekly effort to keep the park clear of trash brought in by weekend vacationers.

The Park Service is constantly going through the dilemma of “development versus preservation”, though the purpose of National Parks, Monuments, etc. is to protect wild spaces development will inevitably have a negative impact. Abbey writes extensively on the impacts of industrial tourism in the parks and describes the changes Arches has undergone: “The little campgrounds I use to putter around reading three-day-old newspapers full of lies and watermelon seeds have now been consolidated into one master campground that looks, during the busy season, like a suburban village”. Abbey goes on to describe the need for comfort while camping including the obnoxious camper vans with their TV’s and generators that far out number the tourists sleeping in tents.

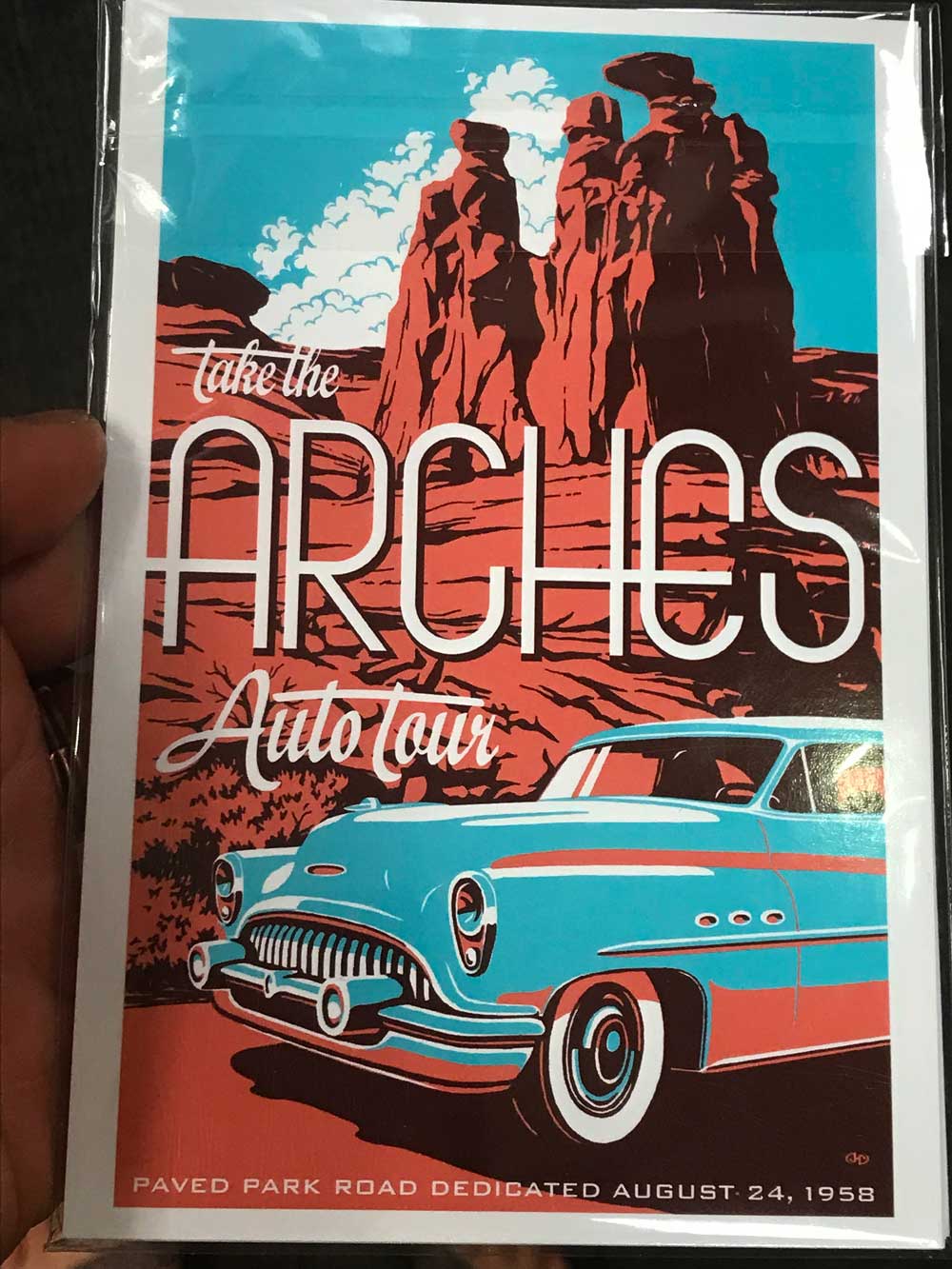

Although there was only one road in the park, Abbey suggested the solution to human environmental impacts was to avoid building more roads and close the park to all motorized travel. A solution he believed would not only help preserve the park but help tourists to enjoy the natural magnificence of the land, “Better to idle through one park in two weeks than try to race through a dozen in the same amount of time.” Of course, Abbey’s visions did not come to fruition and Arches has been built up with a campground in the center and roads weaving through the entire park.

Although there was only one road in the park, Abbey suggested the solution to human environmental impacts was to avoid building more roads and close the park to all motorized travel. A solution he believed would not only help preserve the park but help tourists to enjoy the natural magnificence of the land, “Better to idle through one park in two weeks than try to race through a dozen in the same amount of time.” Of course, Abbey’s visions did not come to fruition and Arches has been built up with a campground in the center and roads weaving through the entire park.

It was not Abbey’s mission to keep people out, but simply help foster a different relationship between humans and the wild. A relationship where everyone was there to appreciate, honor, and understand the parks they visited and as Abbey put it, “leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations”.

It was not Abbey’s mission to keep people out, but simply help foster a different relationship between humans and the wild. A relationship where everyone was there to appreciate, honor, and understand the parks they visited and as Abbey put it, “leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations”.

Landscape Arch. Note the foot path that people have worn underneath the arch despite a sign prohibiting off-trail travel and a fence.

Abbey’s is a valuable lesson that we strive to teach every student who comes up to High Trails. The forest is not our home; it is the home to plants and animals, not to humans. We must leave it as we find it, leave it better than we find it, practice the Leave No Trace principles, and work hard to be stewards of the outdoors.

At High Trails Outdoor Science School, we literally force our instructors to write about elementary outdoor education, teaching outside, learning outside, our dirty classroom (the forest…gosh), environmental science, outdoor science, and all other tree hugging student and kid loving things that keep us engaged, passionate, driven, loving our job, digging our life, and spreading the word to anyone whose attention we can hold for long enough to actually make it through reading this entire sentence. Whew…. www.dirtyclassroom.com

- www.nps.gov/articles/arch-timeline.htm ↩

Comments are closed.